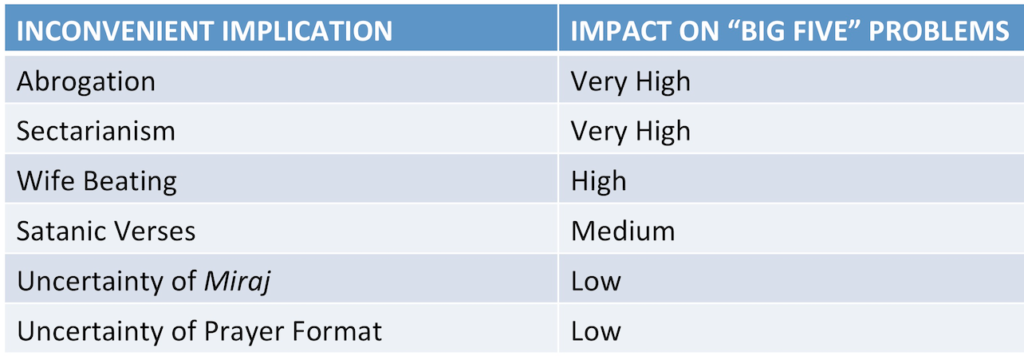

Beyond the three Tragic Errors, there are six additional Inconvenient Implications of Traditional Islam. Each has a varying degree of impact on solving the Big Five problems, i.e. the ability to progress toward higher levels of human welfare; hence, we include an impact rating for each, with higher impact topics discussed first. The impact rating is subjective.

1. Abrogation Muddle

Impact on Big Five: Very High

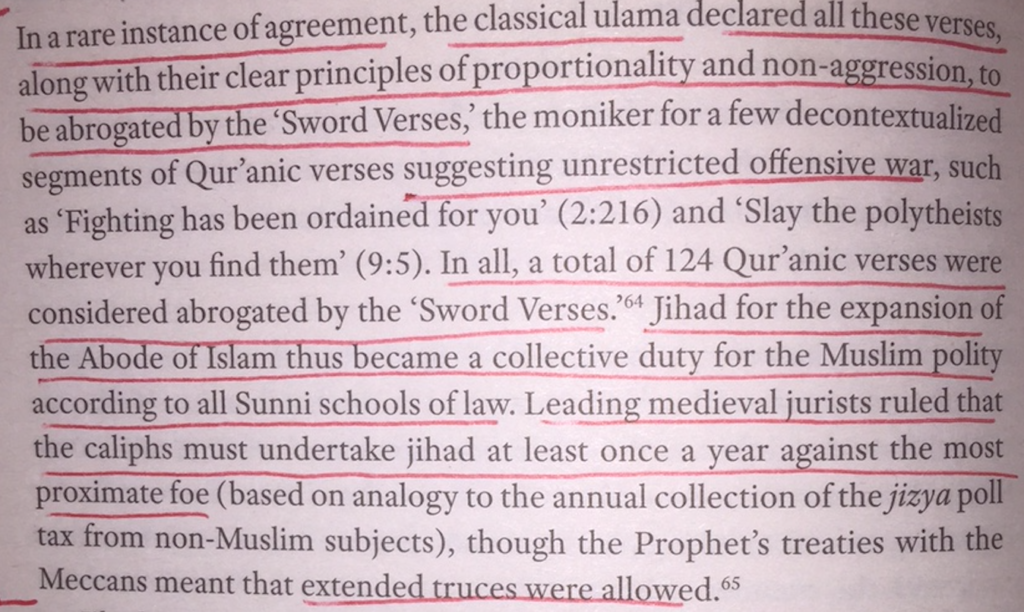

Most ulama believe in the doctrine of abrogation, naskh wa al mansukh, and wrongly invoke it to invalidate crucial Quranic verses. Eminent ulama claimed anywhere between 5 to 500 verses of the Quran were abrogated — how could they differ so drastically on such a crucial topic? The ulama constructed this doctrine, erroneously basing it on a single ayat (Q. 16:101), to resolve the contradictions that resulted in the complex system of Traditional Islam. While some scholars limited themselves to one Quranic verse abrogating another, the majority, including the most respected of the ulama, went down the slippery path of cross-genre abrogation, where Sahih Hadith can abrogate a Quranic verse.

The dangerous doctrine of abrogation is used by many leading ulama to untangle the complex system. A giant of Traditionalist scholarship, al-Suyuti (d. 911/1505) quotes the consensus of earlier scholars that “no one should try to interpret the Book of Allah before learning its abrogating and abrogated verses”.1 All the four major Traditionalist schools (madhhabs) accept abrogation (naskh), that a Quranic ayat can be abrogated. Shockingly, according to a leading scholar, three out of the four madhhabs also believe a strong Sahih Hadith can abrogate the Quran.2, i.e. cross-genre abrogation. Another leading scholar says, the bodies of substantive law in all the Sunni schools demonstrated countless instances of this occurring”.3

What does it mean to abrogate? Is it a temporary suspension or permanent obliteration? According to a leading scholar, “Naskh may be defined as the suspension or replacement of one Shari’ah ruling by another, provided that the latter is of a subsequent origin, and that the two rulings are enacted separately from one another”. He also says, “Although there is some debate among scholars as to what exactly it means to abrogate, according to the majority view, it means to obliterate”. Most scholars use the term in the context of a substantial and lasting change to divine or Prophetic guidance. Kamali says, “Naskh is a controversial subject and many of its conclusions that have been upheld on it in the works of some ulama have been questioned by others”.4 Another leading scholar says, “consensus on abrogation was rare. The intangible and ambiguous indications of abrogation meant that there was often little beyond inclination to justify a scholar’s decision to classify a Quranic verse or Hadith as ‘abrogated’ or ‘abrogating'”.5

– Doubting Quranic Integrity

Soon after the Sahih Hadith books were canonized in the 3rd c. AH, the question arose as to how to reconcile them with the Quran. In this convoluted project, the ulama created a hot mess, even on the most fundamental issues on whether the Quranic text is invariant, as discussed in Quran Integrity Debate. Modern scholars are at odds too. For example, returning to the disturbing issue of cross-genre abrogation, where a hadith abrogates an ayat, the popular scholar Kamali says of the four madhhabs, only the Shafii school has a narrower scope, in that only the Quran can abrogate itself, and that a hadith cannot.6 “Thus a textual ruling of the Qur’an may be abrogated either by another Qur’anic text of similar strength or by a mutawatir hadith, and, according to the Hanafis, even by a Mashhur Hadith, as the latter is almost as strong as the Mutawatir. By the same token, one Mutawatir Hadith may abrogate another”.7 However, the topic of abrogation is complex enough that even basic claims of contemporary leading scholars are at odds. While Kamali says only the Shafii school disallows a Hadith from abrogating the Quran, Brown says the Hanafi school disallows it, since “mere authenticated Hadiths thus could not abrogate Quranic verses”.8 Regardless of who is more correct, it underscores the pitfall of a complex system.

More disturbingly, Traditionalist scholars have claimed that the present-day Quran is incomplete and excludes dozens of verses that were once revealed to the Prophet ﷺ but were caused by Allah ﷻ to be forgotten and thus excluded during the compilation of the definitive Uthmanic mushaf. For example, they claim only 73 out an original 200 verses survived in Sura Azhab. They make this claim in a mistaken attempt to reconcile Hadith that either refer to Quranic verses that do not exist or Hadith that explicitly suggest that some suras were longer than exist in the Quran today. A comprehensive review of this and other facets of the abrogation muddle is done by Louay Fatoohi in Abrogation in the Qur’an and Islamic Law.

– Post-Canonization Trap

In the first century of Islam, it is likely that there was almost no abrogation since there was no complex system. Rare clear cut cases did exist, such as the verse that calls for a change in prayer direction from Jerusalem to Mecca (a topic which has spawned a debate that is unrelated to abrogation, as discussed in ‘Is Mecca = Becca’ in Historical Truth?). To the degree there were multiple ayats on a topic were revealed to address varying circumstances over a multi-year period, such as condemning alcohol, it was clarified by the Prophet ﷺ, as discussed further below. But as time went on, and as the complexity of the religion grew in lockstep with the temporal distance from the Prophet ﷺ and the vast geographical spread of the religion, there was greater need to rely on abrogation to untangle the complexity. As discussed in Historical Truth, the birth of the complex system was a result of the canonization of Sirah and Sahih Hadith books in the third century AH (to recall, in the first century AH there were no such books). Meanwhile the Umayyad and Abbasid rulers were looking for a clean, simple religious narrative that they could standardize on in order to better control the subjects of their far-flung and fractious empire. It is likely that to resolve conflicts of opinion in a manner favorable to their shared interests with the rulers, the ulama concocted an elaborate doctrine of abrogation.

Across time and region, Traditionalist scholars held widely varying opinions on how many ayats were abrogated, which ones were. As noted earlier, the range of estimates is as wide as between 5 to 500. The early scholars were at the high end of the range and the number narrowed over the centuries. For al-Zuhri (2nd/8th century) it is 42, for al-Nahhas (4th/10th century) it is 138, for Ibn Salama (5th/11th century) it is 238, Ibn al-Ataiqi (8th/14th century) it is 231, for al-Suyuti (10/16th century) it is 20, for Shah Wali Allah (12th/18th century), it is only 5.9

One unhelpful attempt to explain the variance in the number of abrogated verses across time is provided by the Daul Uloom Deoband, a leading south Asian Islamic university, “One of the main reasons behind the difficulty of this subject is the difference of opinion between the early and later scholars about the technical meaning of the word naskh ‘abrogation’. What is known from some investigation into the speech of the Companions and the Followers is that they used the word abrogation in the common linguistic sense, namely, the removal of one thing by another, and not in the sense taken by legal theorists, i.e., that one verse has abrogated another verse and it is not acceptable to act upon that verse anymore”.10 This begs the question why did the technical meaning of the word naskh migrate so significantly across time, and are there other words that mutated similarly. The Deobandis rely on the view of Shah Wali Allah that only five verses were abrogated, and that too by another Quranic verse, not a Hadith.11

– Dangerous Dissonance

The license to abrogate was abused by the ulema to promote pet views under religious cover.

For example, the idea that all monotheists who perform good deeds go to Heaven, even if they are not Muslim, is expressed by verses 2:62 and 5:69. However, many Traditionalist scholars disagree stating these verses have been abrogated.

Another one – the infamous ‘sword verses’ or ayat as-saif, (Q. 2:216, 9:5), which were most likely originally revealed in a particular circumstance of self-preservation, at a time when the early Muslims were experiencing conditions of extermination. However, they were later hijacked and repeatedly abused by ruthless rulers who waged war, i.e. the lower form of jihad. Such rulers were behaving in an unIslamic manner, possibly following a policy that resembles what eminent Western scholars today label post-Westphalian ‘offensive realism’.12 Such Muslim rulers relied on Traditionalist interpretations — that these sword verses abrogate the numerous peace-promoting verses in the Quran.

– How to Ban Booze?

Is naskh necessary to justify banning alcohol, or is it sufficient to arrive at that orthodox position through the Hadith route? How should we understand the varied ayat on alcohol? One verse simply affirms trees provide both food and intoxicating drink (Q. 16:67). Another says intoxicants have greater harm than good (Q. 2:219). Another says do not pray while intoxicated (Q. 4:43). Two more ayats highlight the downside of alcohol and ask the believers to shun it (Q. 5:90-91). Some non-Traditional Muslims note that a close reading of the verses condemns alcohol only when consumed in conjunction with gambling, consistent with prohibitions in Jewish law, but given the vagaries of the Dictionary-and-Grammar Problem it is hard to know from the Quran alone what the intention of revelation was. The ulama interpret 5.90-91 as conclusively banning all intoxicants, not just wine, by one of three methods – naskh, or Hadith, or both. The ulama assume they know the chronology of these verses and use naskh. They agree that the earlier verses did not explicitly forbid alcohol, but later verses did and hence permanently abrogated the earlier ones. However, without relying the doctrine of abrogation, there are numerous sahih Hadith that condemn either intoxicants or the state of intoxication. Some Hadith condemn any intoxicant, even in the smallest quantity. Others condemn only wine but not other intoxicants like beer, which leaves room for moderate consumption of all but wine, short of antisocial intoxicated behavior. A fascinating review of these early debates is found in Najam Haider’s Contesting Intoxication: Early Juristic Debates over the Lawfulness of Alcoholic Beverages, Islamic Law and Society, 2013. Some ulama insist you need both Hadith and naskh to justify a permanent ban.

BioIslam’s stance? BioIslam advises against alcohol consumption, but without relying on any of the three strategies used by the ulama – abrogation, chronology of revelation, and hadith. Being a pro-science interpretation, it is against alcohol since it is relies on recent evidence from both medical and social science regarding the downsides of consumption. We also note that a critical reading of the verses 16:67 and 2:219 suggests none of them explicitly permit alcohol; instead they merely observe it is a fact of life. These verses are clearly more lenient, perhaps because early pagan converts to Islam continued with their pre-Islamic ways of alcohol consumption. But, tempting as it is, the exact chronology of these (or any other set of verses) is not possible to ascertain without relying on post-Quranic sources and thus getting mired in the complex system problem (a challenge for the intellectually adventurous is to assemble an approximate chronology, relying on the context supplied by the Quran itself). Using the Traditional chronology, sura 5, al-Maidah, which contains strong condemnation of alcohol, was revealed late, in around year 20 of the 23-year Prophetic period, which is puzzlingly late. Thus, given the varied stance of the ayat and the late ban on booze, we should let the science speak, and it has spoken against it.

– Why Not Abrogate More?

Most disappointingly, to the degree that the Traditionalist ulama embraced the doctrine of abrogation, why did they not use this powerful tool to outlaw Riq-Slavery or Wife Beating? To the best of our knowledge, there was no serious discussion among the ulama on using naskh to rid the faith of these vile practices.

BioIslam’s stance? The doctrine of abrogation is wrongheaded. All problems that naskh is invoked to solve can also be solved by using the linear induction-illustration method of BioIslam, without getting mired in the complex systems problem. To the degree that we need to know the context, causes and chronology of verses to resolve an issue, that might be available from within the Quran itself, and when it it not we must rely on science to speak to the issue since God/Allah ﷻ continues to guide us through it.

2. Stoking Sectarianism

Impact on Big Five: Very High

Sectarianism has ancient roots and remains rife in the Muslim world today; it is killing us, literally. Geopolitics has always exacerbated it, such as the sectarian overlay to the medieval Ottoman-Safavid and modern Saudi-Iran tussles. Yet, we must face up to the unpleasant fact that its roots lie in the Hadith books. However, the Quran strongly condemns sectarianism (6:159). Here are examples of how blind faith in the best of the post-Quranic books stokes sectarianism.

Three Key Disuputes: At the heart of the Sunni-Shia dispute lie three core issues. First, what was the content of the Final Sermon? Second, is the Hadith of Ghadir Khumm reliable? Third, if it is a reliable Hadith, what does the crucial word mawla really mean?

Final Sermon’s Content: First, before the Prophet ﷺ died, he delivered a Final Sermon. There is dispute as to what was the exact content of this sermon. The mainstream Sunni version has the Prophet ﷺ saying, among many things, that his community should follow the Quran and the Sunnah, where Sunnah is widely interpreted to mean the consensus of the majority of scholars on what the Prophet ﷺ said or did. The Shia believe that instead of the ambiguous Sunnah the Prophet ﷺ designated a family member, Ali, as a leader in that same sermon. Further, they claim the Prophet ﷺ endowed him secret esoteric knowledge that would preserve the pristineness of the religion through time, i.e. prevent it from the earthly corruption of impious rulers (that has in fact characterised much of Islamic and world history). The Sunnis reject the claims of the Shia.

Ghadir Khumm Hadith — Second, an additional and perhaps even larger claim is that after that sermon was delivered, as the Prophet ﷺ was on his way back to Medina, he is reported to have stopped at a pond called Ghadir Khumm. This pit stop is believed to have been prompted by the revelation of Q. 5:67 which some scholars interpret as a command to identify a successor to the Prophet ﷺ. There is massive disagreement on what, if anything, he said there. All Shia sources record this Hadith, “Of whomever I am the mawla, Ali is his mawla too”.[/efn_note]We use the common term Shia throughout. The correct academic terminology uses Shi’i as an adjective and Shi’a as reference to the community.[/efn_note] The Sunni Hadith books by Imams Bukhari and Muslim do not record this Hadith, but the credible Sahih Hadith books of al-Tirmidhi, Ibn Maja and the additional Hadith collection by the highly respected al-Naysaburi and Ibn Hanbal do13 It is odd that an event of such importance would not feature in all Sahih Hadith books when much less significant reports were included. The most elaborate account of the event of Ghadir Khumm was offered by a early-11th century scholar, which begs the question why not sooner. Over time the Shia remembered it via celebrations, and rulers exploited these sentiment to boost their legitimacy; one ruler sponsors a large public celebration, Id al-Ghadir, one that continues in some regions.14

Mawla’s Meaning — Third, to the degree that the Hadith of Ghadir Khumm is valid, there remains a large problem — what does the word mawla mean? According to one scholar it could mean any of the following: master, patron, friend, client or protege.15 Shi’a prefer the first two interpretations, Sunnis the remaining ones. This is a prime manifestation of the Dictionary Problem that we discussed earlier.

Ten in Heaven — A fourth non-core dispute involves another Hadith. The Sunni Sahih Hadith books (but not the Shi’a ones) claim that the Prophet ﷺ specified a list of ten sahaba who were promised paradise (jannah). However, later, some of these ten fought on opposite sides of the civil war. Clearly one side was very much in error in that fitna. So how could all of those sahaba then find a place in jannah? Could they not have argued again or at least sat out the war if they were uncertain which side was wrong, as clearly one side was. The Shi’a reject this Hadith stating “Sunni hadith literature famously names a list of “ten promised Paradise” (the first four caliphs, Talhah, Zubayr, Sa‘d b. Abi Waqqas, ‘Abd al-Rahman b. ‘Awf, Abu ‘Ubaydah al-Jarrah and Sa‘id b. Zayd). However, the report is doubted in the Shi’i tradition for a few reasons. First, the hadith is considered a “solitary report,” which some theologians did not consider to be valid in establishing theological tenets. Second, the only Companion who may have narrated this report was Sa‘id b. Zayd who included himself in the list”.16

How do we know which version of the Final Sermon document is more correct? Or what the word mawla really means? There is no objective and reliable method of authenticating this today. If the Sunni Sirah books are accurate, the Shia claim is wrong. But insisting on accuracy of those Sunni books has the troubling implications about the Prophet’s personal life, as noted earlier. You can’t have it both ways.

BioIslam’s stance? BioMuslims reject all Traditional sectarian identity, they are neither Sunni nor Shia. They believe Sirah books and documents like the Final Sermon might possibly contain much error, even more so than the Sahih Hadith books since, unlike the latter, they did not go through the isnad vetting process, imperfect as that process might have been. Therefore, we can not be certain of what the Prophet ﷺ said to whom, and what exactly certain keywords meant, on this topic. However, we do know that the Quran does not endorse any particular form of government or power sharing, either on the secular or spiritual fronts, and explicitly condemns sectarianism (6:159). Therefore any squabbles about the transition of power from the Prophet ﷺ to others are to be lamented as human folly, even when the best of the sahaba are involved.

3. Wife Beating – In Most Translations

Impact on Big Five: High

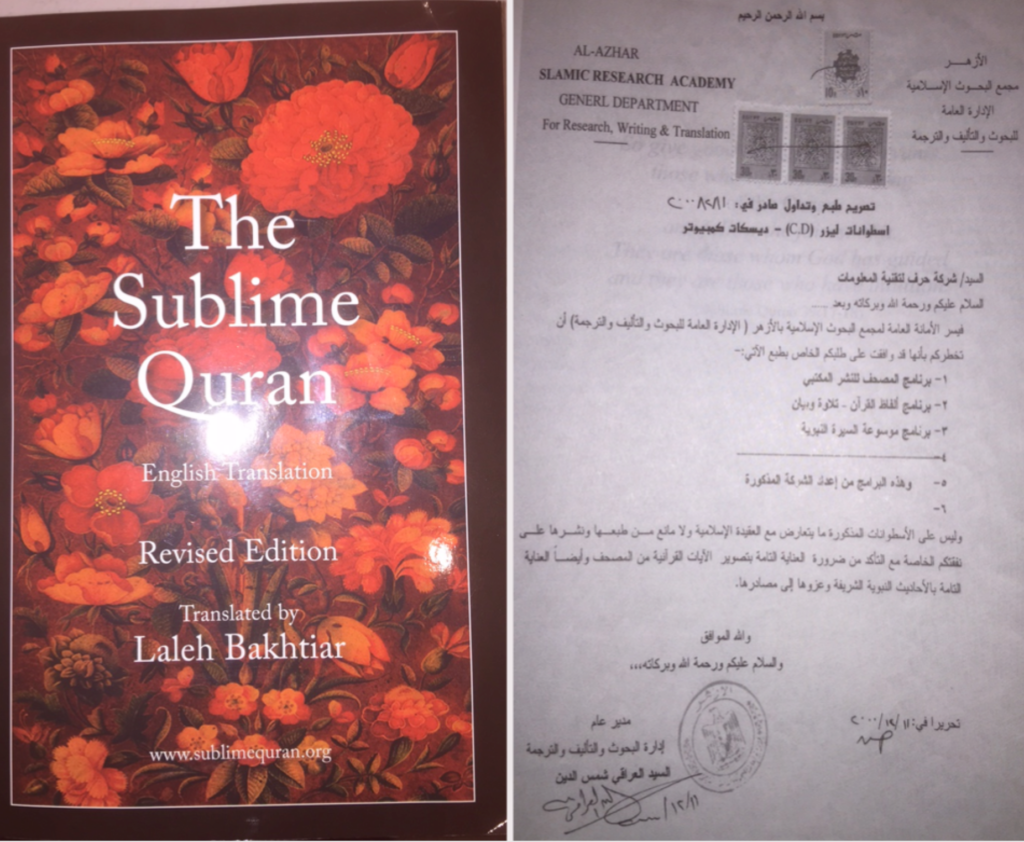

Almost all English translations of the Quran, that the Traditionalists rely on, suggest that verse 4:34 gives permission to hit your wife, under certain circumstances. Tafsir commentaries by scholars have never denied this but have moderated the intensity of the verse – some suggest it might be a light symbolic beating, others suggest it could be more severe than that, yet light enough to not leave visible bruises. The emotional and psychological scarring is not discussed, which is unfortunate but unsurprising for that harsh era. One scholar says, “There is not a single pre-colonial Islamic jurist or exegete who interpreted 4:34 in a way that forbids husbands from hitting their wives… In the end, Muslim jurists and exegetes created space for hitting wives that encompassed symbolic hitting with a handkerchief or toothbrush, as well as beating with one’s hands, sandal, switch or whip”.17

Even the esteemed al Ghazali (d. 505/1111), highly respected as a formidable intellectual and orthodox Sufi endorses this interpretation of what is allowed in the last resort, “… then he should beat her but not excessively, that is to the point that he would inflict only pain but without breaking a bone or causing her to bleed. He should not strike her face for that is forbidden”.18

To be fair, Traditionalists point out there is no record in the Sirah or Hadith of the Prophet ﷺ ever striking his wives. But neither is there much condemnation of those who did; it is very likely that there was much domestic violence back then (in all societies), far more so than the high level that sadly continues to exist. Also, while Traditionalists claim that the Sahih Hadith books are accurate, they do not claim they are an exhaustive record of what transpired back then — which leaves open the possibility that incidents or discussions of wife beating were not recorded.

Importantly, a dissenting translation by a woman, The Sublime Quran by Laleh Bakhtiar, which has been approved through a fatawa issued by the famous seat of Islamic learning, Al Azhar University in Egypt (pictured below), relies on an entirely different meaning of the key word daraba, to “strike a new path” rather than just “strike”. BioMuslims accept Bakhtiar’s translation might well be a better representation of the truth, not because she is a better translator (many scholars would argue she is not) but because the Traditionalist translation of the verse is so inconsistent with the Quranic ethos. The likely culprit — the “Dictionary Problem”, that we discussed earlier in Simple v Complex System.

BioIslam’s stance? This is clearly a high impact problem. Domestic violence is a huge problem in Muslim countries (and certainly in non-Muslim ones, too). However, in the former, discussion of it is a social taboo. You rarely hear this discussed or condemned in the Friday sermon, the Jumma Khutba. Why? Could it be that doing so begs the Dictionary Problem?

4. Satanic Verses – Sanctity of Revelation

Impact on Big Five: Medium

BioMuslims reject the story of the Satanic Verses. However, Traditional Muslims must reluctantly accept it since it is cited by the greatest of Traditionalist scholars in the first several centuries of Islam — they include Ibn Ishaq (159/770), al Tabari (310/923), Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani (d. 852/1449) and most notably Ibn Taymiyya (728/1328). The latter two scholars held the honorific, Shaykh al Islam, hence their opinions are weighty. “The early Muslim community believed almost universally that the Satanic verse incident was a true historical fact… for the early Muslims, the Satanic verses incident was something entirely thinkable”, a leading scholar states.19.

From Acceptance to Anathema — Can truth shape shift? There has been a major shift in the consensus of the ulema on this topic between the first 200 years and the last 200 years. “How was the Satanic versus incident transformed in Muslim consciousness from fact into anathema, from something entirely thinkable into something categorically unthinkable. How did the truth in the historical Muslim community go from being the one thing to the opposite thing… at whose hands did this happen?”.20

Much Ado About Something — Interestingly, the version of the story that Traditionalists find controversial was not viewed as a major controversy until it was popularized in the late 19th century by an orientalist scholar and Christian minister, William Muir. In the 1980s, it was fictionalization by Salman Rushdie in a book, The Satanic Verses; an excessive fatwa of death was pronounced against the author, and the story then exploded. Many bigoted statements are made about Islam (and other religions) but they fade away without much ado. However, given the passions inflamed by this story, and given the centrality of the sanctity of revelation, it is reasonable for both Muslims and non-Muslims to ask whether there is any merit to it. Also, it is important for a Traditionalist Muslim to ask why respected scholars of Traditional Islam were so comfortable with it for so long. And why do modern authors of Islamic history or sirah books pretend like it never occurred?

There are three versions of this story, which we label the “Clean Sweep”, the “Partial Hearing” and the “Dicey Deception”. Most contemporary Traditionalist scholars only accept the first version. But some scholars who Traditionalists consider as highly respected, including the celebrated Ibn Taymiyya, believe in the second and third.

Clean Sweep — In the Sahih Hadith book of Bukhari, it is noted that when Sura Najm (Sura 53) was recited by the Prophet ﷺ during the month of Ramadan in the fifth year of the Hijra, in the last verse of the Sura, where there is a call to prostrate before God/Allah ﷻ, the Quraysh (who were opponents of the earliest Muslims), they too prostrated alongside the Muslims. This was a first for them, and an anomaly, since they did not convert to Islam at this time. It presumably occurred since they were overwhelmed by the power of the Sura. This is celebrated by Muslims as a demonstration of divine power and beauty. Note that this version cites what the Quraysh did but not why they choose to do so. Later versions build upon Bukhari’s story in an attempt to explain why.

Partial Hearing — This version is cited by the great historian al Tabari, and by the renowned hadith scholar Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani. These scholars believed that after verse 20 of Sura Najm was recited by the Prophet ﷺ, Shaitan recited aloud two additional verses that do not exist in the present day Quran. These verses affirm the intercessory power of three pagan dieties of pre-Islam – al Lat, al Uzza and al Manat. These scholars believed that God/Allah ﷻ made it such that the Muslims did not hear these Satanic verses, and only the non-Muslims did. Based on this partial hearing, the Quraysh prostrated alongside the Muslims. Interestingly, Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani (d. 852/1449) posits this explanation centuries after Imam Bukhari (256/870), and given the high status of his scholarship it can not be dismissed by Traditionalists, not without tossing out the rest of his corpus. Since Asqalani must surely believe in Bukhari’s work, he does not negate it, and presumably builds upon it.

Dicey Deception — This is a highly problematic version posited by one of the greatest scholars of Traditional Islam, Ibn Taymiyya about five centuries after Bukhari. Again, since Ibn Taymiyya must surely be expert in Bukhari’s work, he does not negate it but presumably builds upon it. In this version, the reason why the non-Muslim Quraysh prostrated is that they did in fact hear those additional verses about the three pagan dieties be recited by the Prophet ﷺ. When the Muslims pointed out to the Prophet ﷺ that this was contrary to his message of strict monotheism, the Prophet ﷺ realized that he had been tricked by Shaitan who had spoken in the voice of Jibreel ahs (Gabriel), the angel of revelation. Thereafter the Prophet ﷺ abrograted the two satanic verses. The problem with this version is that it compromises the purity of revelation, and suggests it is easy for the Shaitan to dupe the blessed Prophet ﷺ, contradicting a key article of faith for Traditionalist Muslims.

So why does Ibn Taymiyya accept this version? Because he believes its acceptance is necessary to explain the meaning of two other verses in Sura Hajj, 22:52-53. Ibn Taymiyya believes it is not possible to explain the verses in Sura Hajj without his problematic interloper explanation of the satanic verses.

Q 22:52-53, Saheeh International translation, says: “And We did not send before you any messenger or prophet except that when he spoke [or recited], Satan threw into it [some misunderstanding]. But Allah abolishes that which Satan throws in; then Allah makes precise His verses. And Allah is Knowing and Wise. [That is] so He may make what Satan throws in a trial for those within whose hearts is disease and those hard of heart. And indeed, the wrongdoers are in extreme dissension”.

Q 22:52-53, Abdul Haleem translation, says: We have never sent any messenger or prophet before you [Muhammad] into whose wishes Satan did not insinuate something, but God removes what Satan insinuates and then God affirms His message. God is all knowing and wise. He makes Satan’s insinuations a temptation only for the sick at heart and those whose hearts are hardened- the evildoers are profoundly opposed [to the Truth].

An extensive discussion of this topic is in The Study Quran21 which concludes thus on page 844, “the incident of the goddesses obscured rather than explains the verses it claims to be connected with… the accounts offer a strained and implausible chronology… accounts themselves contradict one another in substantial ways…” (phrases deleted to highlight the complexity of the problem, hence it is best if you read the source for the full text). It appears that in an attempt to resolve one problem, the ulama have created another – adding to the needless complexity of Traditional Islam.

BioIslam’s stance? Although the Clean Sweep version is simple and consistent with the Quranic ethos regarding the inspirational power of the Quran and the rhythmic beauty of its recitation, it is not particularly helpful in illuminating any Latent Principle, hence unimportant. However, the Partial Hearing and Dicey Deception versions are rejected by BioIslam, not just because they are inconsistent with the Quranic ethos but also since those Traditionalist scholars were likely building their complex arguments upon a flawed foundation.

5. Uncertainty of Miraj

Impact on Big Five: Low

The Miraj is one of the most important events during the lifetime of the Prophet ﷺ. Yet there is surprisingly little certainty about two key elements of it: in what year of prophecy did this occur, and whether it was a physical journey or metaphorical one?

This uncertainty stands in contrast to great certainty that is projected in less important aspects of his life. For example, traditional scholars debate when exactly it occurred – estimates range from 1 to 7 years prior to the Hijra. Even though there was no precise calendar record keeping in those days, the range of possible dates is simply too wide to be credible, especially given the far greater certainty ascribed to other key events during prophecy, such as the year of Hijra or year of death of the Prophet ﷺ. Also, the story of how the number of rakat in prayer was settled upon during the Miraj is oft told with relish and vivid detail — how could such clairty coexist with the foggy timing of it? Also, there is scholarly debate on whether the Miraj was a physical journey to Al Aqsa or metaphorical. Given Sunni belief that the edict for five prayers was established during this event, after allegedy protracted negotiation, it is hard to believe that the Prophet ﷺ, may peace be upon him, would have left it open as to whether it was a physical or metaphysical journey. BioMuslim’s believe he would have specified it, but the surviving books available to us today are incomplete on this, i.e. there has been a loss of information and clarity along the way. Once again, the certainty of the Traditionalists on this front is hard to justify.

BioIslam’s stance? Although BioMuslims accept the broad outline of the Miraj narrative, they do not take a position on whether this was a physical or metaphorical journey, and when exactly it occurred, since we have no way of knowing for sure and since it is not relevant to addressing the Big Five challenges.

6. Uncertainty of Prayer Format

Impact on Big Five: Low

If there is one area where you would expect consensus, it would be how exactly did the Prophet ﷺ pray. Despite the fact that the people joined the Prophet ﷺ in frequent public prayer, there is a surprising lack of consensus on the format. Although there are many differences in opinion between the Sunni and Shia, it is more relevant to our analysis that there are puzzling differences between the four Sunni madhhabs. So we skip past issues on which the Sunni are united in their differences with the Shia (examples of Sunni-Shia differences on which Sunni are in consensus: 1) the five Traditional prayers must be prayed at five different times, not combine them into three times, as the Shia do, 2) it is best to proclaim ameen after the sura fatiha, which the Shia do not, 3) that is best to pray extra tarawih prayers in congregation during Ramadan, as opposed to pray nawafil privately at home, like the Shia do, 4) that you must break your fast before praying maghrib while there is still some light, and there is no reward to wait until additional darkness descends, as some Shia do.)

Where to place hands during prayer? The Shia and the Sunni-Maliki position their hands down the side (sadl), while three out of four Sunni schools fold them at the waist (qabd). Even with qabd, there is a minor debate about whether to fold above or below the navel. It would have been pretty clear to observers in which specific manner the Prophet ﷺ prayed, so why the disagreement? Perhaps he did both – which would be consistent with the remarkable flexibility of the Quranic ethos — but that is not the position of any madhhab or sect. Also, the people in closest proximity to the Prophet ﷺ, his family and the denizens of Medina, are likely to remember best. That would suggest the Shia and the Malikis are correct – the Shia link back to the Prophet’s family through Ali, the ahl al-bayt, and the Maliki madhhab has Medina as its epicenter. Two of the four Khalifa Rashidun, the rightly-guided rulers according to tradition, would have been in the sadl camp. However, since only about 20% of global Muslims are either Shia or Malikis, thus using the sadl format, is the majority praying in a manner different from the Prophet ﷺ?

Other surprising variations in prayer format exist. Should the basmala be recited before each sura in the prayer or just at the start of sura fatiha? If required, should it be recited silently or aloud? When required to be recited before the fatiha, is it an integral part of the fatiha or separate from it? Opinions on this simple topic vary by madhhab and scholars have expended many pages documenting these differences.22 As an aside, there was a debate on whether the fatiha is even a part of the Quran at all, as discussed in Quran Integrity Debate.

The followers of the Shafii and Hanbali madhhabs raise their hands to their ear during the takbir before going into ruku, the Hanafis disagree. There is disagreement on the timing and number of rakat in witr prayer. As noted by one leading scholar, the differing positions are backed up by hadith. “Both of these Hadiths appear to rest on solid, authenticated chains of transmission and seem clear in their meaning. And they also completely contradict one another. The issue of raising one’s hands in prayer thus provides an ideal example of the very frequent clash between contrasting Hadiths”. (Brown, Misquoting, p 104). Traditionalist scholars continue to stir debate on this topic; for example a respected Hadith scholar, Shaykh Nasir-ud-Din al Albani (d. 1999), believed the mihrab, the prayer niche, is an innovation (bid’a) and it is licit to pray in a mosque with one’s shoes.23

Another puzzle is the qunut gesture within fard prayers. Some schools allow a specific duaa called the qunut before the sajda, a special invocation which might contain prayers for or against a group of people, or a curse against an adversary. There are many disagreement on qunut, whether this practice for the Prophet alone or for his followers too, whether to perform it before or after the ruku, whether it can only be performed with the final witr prayer or in conjunction with other prayers too, whether it can be performed year-round or only in certain months. The Hanafi madhhab believes all qunut traditions were abrogated by Q. 3:128, a verse that forbids invoking curses, but incorrectly reinstated later during the first fitna. But those who disagree think that the ayat only obsoletes qunut for obligatory prayers but remains valid for the optional witr prayer.24

The only sensible explanation for all this dissonance – the books from which we derive this inconsistent guidance are either inaccurate or incomplete. Although these surprising variations are inconsequential to addressing the Big Five challenges, they are instructive only because you would expect that if ritualized five daily prayers were a regular component of daily life for the sahaba, then they would all have converged onto one format and preserved it through the oral tradition that Traditionalists take pride in. What is not surprising — the complex system continues to muddy the message.

BioIslam’s stance? BioMuslims do not take a position on which prayer format is most authentic since science has no bearing on this. It does not matter as long as the intention is to praise and thank our Creator. As a practical matter, BioMuslims simply follow along with the conventions that their family and friends have agreed upon, or that which they inherited from their parents.

- Louay Fatoohi, Abrogation in the Qur’an and Islamic Law, p. 2.

- Kamali, M.H., Principles of Islamic Jurisprudence, p. 142 ???.

- Brown, J.A.C., Misquoting Muhammad, p. 100.

- Kamali, M.H., Principles of Islamic Jurisprudence, p. ???. Also see his book Hadith Studies, p. ???].

- Brown, J.A.C., Misquoting Muhammad, p. 99.

- Kamali, M.H., Hadith Studies, p. 128.

- Kamali, M.H., Principles of Islamic Jurisprudence, p. 142.

- Brown, J.A.C., Misquoting Muhammad, p. ???.

- Khaleel Mohammed, Muhammad Al-Ghazali’s View on Abrogation in the Qur’an, Concordia Journal of Religion and Culture, Spring/Winter 1996, Vol 10, p. 47-62.

- Deoband.org, Abrogation in the Quran, 4 Nov. 2010, p. 2.

- Deoband.org, Abrogation in the Quran, 4 Nov. 2010, p. 5-6. Shah Waliullah al-Dahlawi claimed the following five verses are considered abrogated: al-Anfal 65 by al-Anfal 66 / al-Mujadilah 12 by al-Mujadilah 13 / al-Baqarah 180 by al-Nisa 11 / al-Ahzab 50 by al-Ahzab 52 / al-Muzzammil 1 by al-Muzzammil 20.

- Offensive realism best explains international relations in the post-Westphalian era, according to one of the leading scholars in the field. See John Mearsheimer’s The Tragedy of Great Power Politics.

- Kecia Ali in Islamic Concepts says Ali as mawla is reported in the Hadith books of al-Tirmidhi, ibn Maja and ibn Hanbal. J.A.C. Brown in Hadith, 139, says it is reported in al-Tirmidhi and al-Naysaburi. Both authors agree it is not listed in the two Sahihayn, Bukhari and Muslim, yet both would consider these other Hadith compilers as credible. Ali leaves open the meaning of mawla. Brown reports it as “master”.

- Haider, Najam, Shi’i Islam, An Introduction, p. 60-63.

- See “The First Muslims” by Prof. Asma Afsaruddin, p. 14-15 and p.203, for the varied meanings of mawla and for which Hadith books include and exclude the Ghadir Khumm incident.

- Nakshawani, S.A., a popular Shia Imam in “The Ten Granted Paradise”.

- Ayesha Chaudhry, Domestic Violence and Islamic Tradition.

- Etiquette of Marriage, second book in The Revival of the Religious Sciences, al Ghazali, translated by Madelain Farah, Univ. of Utah Press, First Edition, 1984, p. 105.

- Shahab Ahmed, What Is Islam?.

- Shahab Ahmed, Before Orthodoxy?, p.3.

- Seyyed Hossein Nasr, The Study Quran.

- A summary of differences between madhhabs on how and when to recite the basmala is found in Najam Haider’s The Origin of the Shia, p. 79.

- Stephane Lacroix, al-Albani’s Revolutionary Approach to Hadith, ISIM Review, Spring 2008.

- Haider, Najam, chapter on Curses and Invocations, The Origins of the Shia, p. 98-99.