How Do We Know Our Past?

To explain our present predicament, we need to dispassionately assess our past. Where does our knowledge of our glorious Islamic past come from? What underpins the assertions of our religious leaders? How sure are we about what really transpired some fourteen centuries ago? Our conception of the past can be no better than the veracity of the books we rely on since that is the only authentic link between ‘back then’ and ‘right now’. Of course, as noted earlier, we axiomatically believe 1) the Quran encodes latent wisdom for eternity, 2) the aural-Sunnah is authentic.

The big question — how to translate and interpret the Quran, in the context of the Authenticity Assumption, the Cult of Certitude, the Dictionary Problem, and the Abrogation Muddle, all of which are interwoven challenges? The immediate question – are any of the post-Quranic sources authentic enough to assist in mining the profound wisdom latent in the holy Quran? To preview our conclusion, none of the sources is reliable enough to assist in extracting the Latent Principles or Inside Pillars, but some can aid ex post as examples of Prophetic action.

A Long Dark Tunnel

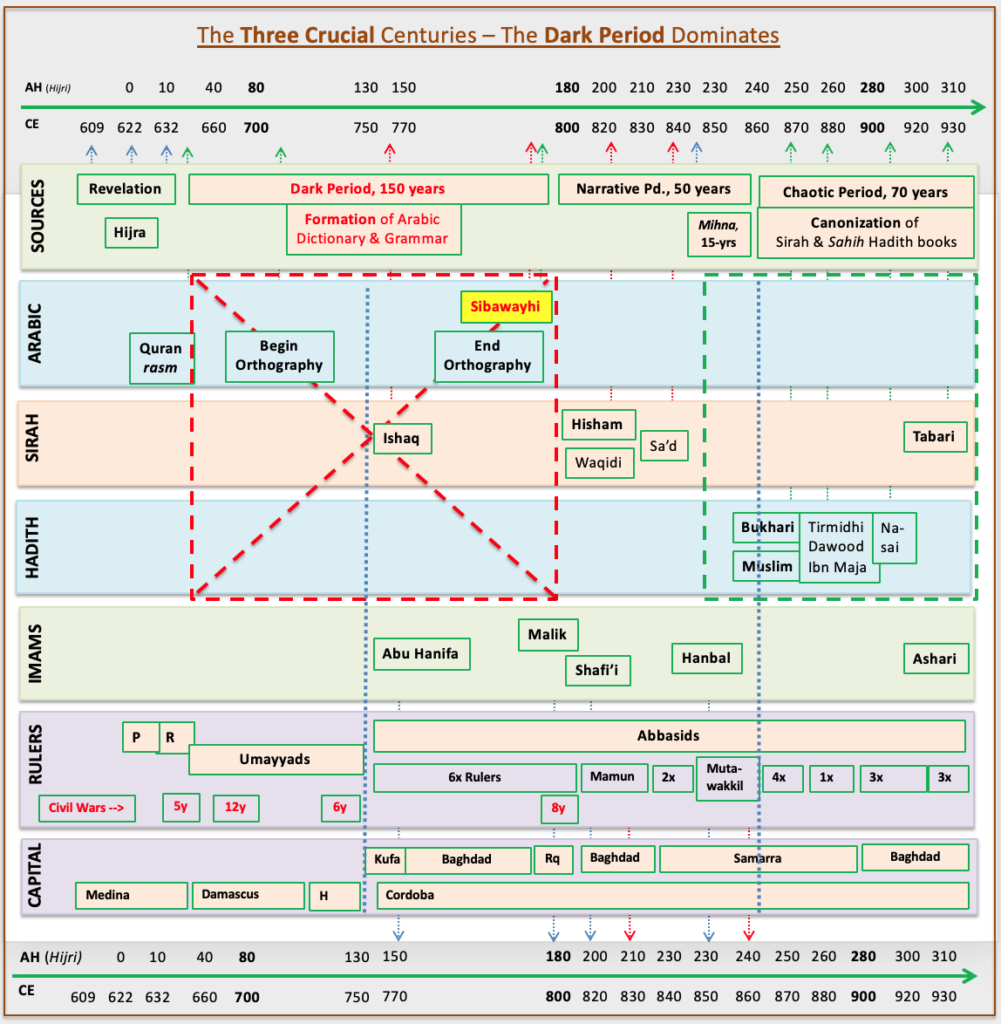

How many written works survive from the first century of Islam (1st c. AH), besides the Quran? Zero. The first surviving work is dated around 200 AH (820 CE), which is a strangely-altered version of a book written around 150 AH. The canonized story of Islam passes through a long mostly-dark tunnel, until it emerges into the full light of history after about two centuries.

Chronology is Key — The books that Traditionalist Muslims deem authoritative after the Quran, specifically the oft-quoted Sirah and sahih Hadith books, were published nearly 200 years after the Prophet ﷺ during the Abbasid empire (which ruled its core territory from around 133/750 to 655/1258). This chronology is key to deciphering our past.1

The pivotal books that the Traditionalists heavily rely on are tightly grouped into a period of about 120 years, from roughly about 190 to 310 AH, and can be sub-divided into a 50-year Narrative Period and a 70-year Chaotic period of canonization, and with the output of the latter period far exceeding the former in both volume and long-term impact. The master narrative of Traditional Islam perhaps owes most to the works of Ibn Hisham, Bukhari and Tabari.

Key works include the earliest books of fiqh, or jurisprudence, by Imam Shafi’i (d. 204/820) in which he attempts to synthesize and supersede the earlier works of Imams Abu Hanifa (d. 150/767) and Malik (d. 179/795). The main sources of biographical information are the Sirah book by Ibn Hisham (d. 218/833), which is a redaction of the mysteriously-vanished work of Ibn Ishaq (d. 159/770), war stories (maghazi) by al Waqidi (d. 207/822) and a book by Ibn Sa’d (d. 230/845). Shortly after this come the sahih Hadith books of Imams Bukhari (d. 256/870) and Muslim (d. 261/875), followed within a decade or so by four additional sahih Hadith works.2 Importantly, the prolific at-Tabari (310/923) weaves it all together into a master narrative. It spans about 10,000 pages in 40 volumes in its English translation, and sets the stage for all future narratives.3

Vast Empire Begs Canonization — Why did the Imams of the third Islamic century canonize, i.e. produce books so definitive that to deny their authority would brand you a heretic? The structural explanation is simple – the vast Arab-Persian hybrid empire would be easier to govern if the divergent sectarian claims were homogenized into a set of canonical books.

The project began with Imam Shafi’i who tried to formalize fiqh into a coherent school of thought (madhab).4 This was in response to a growing gap in fiqh between the Maliki madhab, based in Medina, the historical epicenter of Islamic polity, and the Hanafi madhab that was popular in the Eastern Persia and Central Asia, i.e. the recently extended territory of the empire. In the three or four generations that had passed since the Prophet ﷺ, the Arab-centric original Islamic community of the Hijaz region had rapidly transitioned into a far-flung multi-ethnic, multi-religious one. Imam Shafi’i was deeply concerned by the disparity in the localized practices of the Malikis and Hanafis. This created a crisis of identity and authority, which was the primary societal trigger of canonization.5 He was troubled by their view of the Sunnah, which be believed had accrued innovations over time, versus his view of the original-Sunnah of the Prophet ﷺ. Some differences were visibly trivial, such as where to place the hands while praying – Malikis and Shi’is drop down (sadl), while Hanafis and others fold at the waist (qabd). Others were more consequential, such as the Hanafi permission for moderate consumption of certain types of alcohol like beer.6 He felt both those leading schools had deviated from the original-Sunnah, as suggested by the Quran and other documents and oral traditions, and as best as he can decipher, since he is operating about 200 years after the Prophet ﷺ (b. 150 AH, d. 204 AH).

Imperial Islam – Relying heavily on these texts, Imam Shafi’i attempted to consolidate and universalize the religion-of-empire around the Quran and Sunnah by reconciling the localized interpretations of the Malikis and Hanafis. He was a student of Imam Malik in Medina, and later traveled to Baghdad to study with the leading Hanafi jurist, al-Shaybani, but fell into disagreement with him and moved to Mecca; he later moves to Egypt and back to Baghdad. All of these travels and intellectual encounters prompted a broader effort to reconcile differences between locations and the scholars he encountered, a grand synthesis of sorts. His published a comprehensive treatise on the principles of fiqh, the al-Risala, which set the stage for future scholarship. About one generation later, the canonical Sirah and sahih Hadith books were cemented, and an additional generation later, the first voluminous history of at-Tabari. Since the Malikis and Hanafis disagree to this day with some of Shafi’is views, there is no consensus on what the original-Sunnah is; that which the Traditionalists rely on is in fact a textual-Sunnah, as constructed and canonized by the leading Imams of the third century, with the concurrence of rulers.

Umar’s Fear Realized — Paradoxically, the ruler that Traditionalist Sunnis perhaps revere the most, Umar ibn al-Khattab, also known as Umar I (d. 23/644), “debated a scheme to have the hadith collected into a single text; he decided against this, fearing that it might come to rival the Quran. Some scholars believe that he did collect some Hadith but later erased them.7 His stance was based on the Prophet’s warning to not write down his sayings, something which the first Khalifa Abu Bakr adhered to. So when was the turning point? The systematic collection of hadith appears not to have received official sanction until much later, during the reign of the Umayyad Khalifa Umar, aka Umar II (99-101 / 717-720), who seems to have initiated and partly carried out the task of collating the material.8 What Umar I proscribed, Umar II appears to have prescribed about 70 years later. However, some scholars believe that the father of Umar II, Abd al Aziz (d. 86/705), initiated it during his long reign as governor of Egypt, and Umar II subsequently continued it during his brief two-year reign.9

Does Anarchy Impact Sahihayn? – The assassination of al-Mutawakkil in 247/861 unleashed political anarchy. In its wake, six popular Imams finalized a collection of Hadith books that were accepted by both the ruler and fellow ulama. The sahih collections of Bukhari (d. 256/870) and Muslim (d. 261/875), together known as the Sahihayn, with Bukhari’s book popularly regarded as near-divine. They were the front-runners to an additional four compilations –together, the Sahih Sittah collection of six canonical works, the last of which was by al-Nasai (d. 303/915).10 More importantly, the consensus of the ulama canonized this collection and tarred those Muslims who did not subscribe to them as heretics, thus delivering on the earlier fears of Umar ibn al-Khattab, that the Hadith books would be viewed as crucial to interpreting the Quran. Did heightened political anarchy impact the Sahih Sittah? It is naive to believe it did not.

‘Game of Thrones’ Era — These canonical books were complied in Abbasid lands where there was a chaotic shifting of dynastic power, capital cities, ethnic power bases, and sectarian affiliations; the authors were distant from the Hijaz, where the Quran was originally revealed. Although centered in present day Iraq, the territory of the Abbasid Empire was not only vast but, importantly, was a multi-ethnic mosaic.11 Out of a 30 million population, only 500,000 were Arab – less than 2%.12 In this vast empire, both the political power structure and social structure were in tremendous turmoil. Frequent violent shifts in power had been in play from the early decades of Islamic history. This game of thrones was played out against the backdrop of a big power shift from the western base of the Umayyad dynasty (41/661-132/750) to the eastern base of the Abbasid dynasty (133/750 to 655/1258) in Khurasan (Eastern Persia and Central Asia). On the social front, Islam experienced a breakneck speed of expansion in the first 150 years, from less than 1% of the world to about 10%, from an Arab-centric to a multi-ethnic polyglot population.13

As reviewed earlier in the section on the The Dictionary Problem, the power struggle was preceded by an ethnic rivalry called the Shu’ubiyya movement, a struggle for cultural supremacy which pressured the vanquished non-Arabs of the Sassanian empire into embracing the culture and language of the Arab Umayyads, whom the former viewed as socio-economically inferior. As demographics and ethnic power bases shifted, so did the capital cities of the empire: from Damascus to Kufa to Baghdad to ar-Raqqa to Samarra, during the second and third centuries (and much later to Cairo, after the Mongol rout of the Abbasids).

To compound the chaos, a sectarian schism was at play. The Shia felt betrayed by the Abbasids since the latter started off as Shia revolutionaries against the proto-Sunni Umayyads. But once they gained power in 132/750, they switched over to the proto-Sunni side, since that was the belief system of the majority of their populace, which boosted their mandate to rule. They then claimed to be the divinely sanctioned rulers, Khilafat Allah, of all Muslims. In this period, there was a schism between proto-Sunnis (who later became Sunnis, or more formally, ahlus Sunnah wa al Jamaa, the people of consensus) and pro-Alids the minority group who were pro-Ali, and were later labeled Shi’i, the party of Ali (commonly referred to today as Shia, hence a label we will use for convenience). The Shia only accepted post-Quranic books vetted by Imams who were different from those accepted by the Sunnis. The ‘Imami’ Shia relied on the presumed infallibility of their Imams, more so than the literal text of their preferred books, for validating the Sunnah and historical knowledge.

Victors Write History — As is often said, history is written by the victors. The history of the first century of Islam was written primarily by the Abbasids. Perhaps this has to do with the fact that the Abbasids first discovered paper in the early years of their reign; prior works were written on perishable papyrus and do not survive in the present.14 The earliest post-Quranic books that Traditionalists rely on today were written at least 50 years after the discovery of paper in the third century. By analogy, would you in 2020 be willing to accept the first published work of history on the US Civil War of 1861 under the following scenario: it is authored by a Yankee historian (victor), who redacts (and adds to) an earlier book by a Southern separatist historian (vanquished), and the earlier book is no longer available to fact check? An analogy to the first World War: a German history book (vanquished) written by a French historian (victor). Did the Abbasids write an unbiased history of the tumultuous pre-Abbasid era? Unlikely.

As noted earlier, Ibn Ishaq’s mysteriously-vanished Sirah is available to us only through Ibn Hisham’s redaction – it is a significant redaction since the latter doubts the claims of the former in key topics. In BioIslam’s view, these redactions are very problematic; they taint the integrity of either the redactor or the original author. Ibn Ishaq’s work was mostly completed on the Umayyad-Abbasid fault line, while Ibn Hisham’s is definitely an early Abbasid-era one. Ibn Ishaq was viewed by the later Abbasids as a controversial figure – he is accused of being a Qadarite and a Shia (both ideologically undesirable subgroups by the elite). In addition, he has a very public and personal feud with the famous Imam Malik, where the latter calls him a liar, and another prominent contemporary calls him a heretic.15 Also, although he narrates hadith he is viewed as a highly unreliable Hadith transmitter by Imam Bukhari, the most highly regarded of the famous sahih hadith book compilers, and also by Imams Malik and Hanbal. However, other scholars found him reliable, and some of his hadiths are sourced by the other five out of six compilers of the sahih Hadith collection.16 As another scholar says about the lack of reliable sources, “the degree to which these have been manipulated or altered to fit polemical agendas remains an open question… Faced with such a dilemma, many historians have concluded that substantive research into early Islam is not possible without the discovery of new sources or developments in fields such as archeology or numismatics.17

The Empire’s Heavy Hand

Since the early Muslim empire preceded the era of rapid electronic communication, ruling a vast polyglot territory was no easy feat. One strategy to maintain control was to impose uniformity as much as possible, especially in matters of the mind, notably religion. This phenomenon occurred in the Christian world too.18 The rulers of most empires, including the Abbasids, were concerned that divergent views on religion, in particular conflicts in religious authority, could result in grave civil war, as had occurred during the time of many rulers, including during the cherished rule of the Khulafa-e-Rashidun, the early government of the rightly guided Caliphs. How did people think and act back then? To control the behavior and actions of the people, the rulers had to control their mind. What a psychologist would today formally label the ‘Theory of the Mind’ would in that era have included a large dose of religious views, since the natural and supernatural world, and religion and state, were deeply intertwined in most societies. Successful rulers often instinctually understood this and felt it was necessary to constrain people’s thought and behavior by endorsing a specific flavor of religion to better control their subjects. One mechanism of control was to push religious leaders in a direction compatible with the goals of the state, or to endorse one sect or interpretation as the official state religion.

The Imam’s Socio-political Role – The role of religious leaders has always been important through most of history, across all religions. In an era that had very low literacy levels, one that preceded the printing press and formal classroom education, much knowledge was acquired from the neighborhood religious leader. The Imam or Shaykh was a broad-spectrum community leader and typically wore several hats – religious leader, historian, clinical psychologist and, on a good day, even an armchair philosopher. If Imams varied widely in their interpretation of divine knowledge, there was more likely to be social strife, especially during times of travail, such as famine or war or revolution, all of which were a common occurrence in that era. To sustain a stable empire it was necessary to have social cohesion; that meant substantial uniformity of belief among the ulama. The Christians of that era solved this challenge of cohesion by imposing a strong religious hierarchy presided by the Pope, who allied with rulers to standardize religious dogma throughout the holy Christian empire (which includes the Holy Roman Empire) for over a millennium. And since most societies were organized around a traditional patriarchal model, it is no surprise that most if not all the religious authority was concentrated with male religious leaders.

Pluralism Flourishes In the First Century — After the passing of the Prophet ﷺ in 632 CE, and after the relative theological uniformity of the era of the first four ‘rightly guided’ Khalifas ended in 659 CE, there was increasing diversity in the interpretation of Islam. There was no single widely accepted religious leader, akin to the Pope. There were many Imam’s with varied views on both theological and practical matters, as was to become the norm in the Christian Protestant tradition centuries later. The major schools of thought, Hanafi, Mailiki, Shafi’i and Hanbali did not firmly coalesce until nearly two centuries after the Prophet ﷺ. In an era that lacked modern medicine and nutrition, the average lifespan was a relatively short thirty years, and a century was a long time spanning multiple generations. In this first century, a variety of conflicting interpretations of the religion, i.e. a highly pluralistic Islam, thrived.

Imperial Uniformity In the Third Century — As the game of thrones got more intense, the rulers increasingly relied on and pressured Imams to achieve their governance goals. In the absence of religious uniformity, the rulers observed that their people were often torn apart by religious debate. To maintain control over conflicted populations, some rulers found it effective to pick a side in a religious debate and endorse it as a correct version of the truth, a stencil or template. Then the push was on, to get the rest of the religious leaders, the ulama, and through them the rest of the common people to adhere to that template. The Imams in the empire were incentivized or compelled to subscribe to it. The scholar Talal Asad (son of the popular English translator of the Quran, Muhammad Asad) uses the term ‘orthodoxy’ to denote what we refer to as Traditional Islam. He says, “orthodoxy is not a mere body of opinion but a distinctive relationship—a relationship of power. Wherever Muslims have the power to regulate, uphold, require, or adjust correct practices, and to condemn, exclude, undermine, or replace incorrect ones, there is the domain of orthodoxy”.19 In our current era, in non-democratic Muslim countries, the sermons of the Imams are regularly monitored and circumscribed by the government, and it was likely the case back then too. To enforce convergence of thought around the state-sanctioned religious template, the rulers and Imams worked together to clamp down debate, discourage independent thought, deny academic freedom to scholars, inhibit ideological innovation (bid’ah) and promote the blind imitation of the past (taqlid). Such a ‘dumbed down’ population is easier to control and manipulate. Governance was based on a top-down master-slave model, and the rulers preferred the religious ideology to conform to this authoritarian model. Consequently, instead of being slaves to Allah ﷻ, and to the fine intellect He endows humans with, as the Quran encourages us to, we instead became slaves to despots and their duly sanctioned religious leaders.

The Critical Third Century

Every major religion goes through one or more critical historical periods during which its core texts and tenets are institutionalized.20 For Islam, the first critical period of glorious Quranic revelation ended with the Prophet’s passing in 10/632. The second critical intellectual period occurred during the third Islamic century, around 150/772 to 300/933 which delivered canonical books of Sirah and Sahih Hadith. It is possible that a third critical period began around 2000 spurred by wide dissemination of Islamic knowledge through the Internet.

At the end of the first critical period (10/632), the Muslim community had a written record of the revelation, i.e. the rasm of the Quran,21 plus the hearsay about the Prophet’s statements and actions, i.e. the unwritten (at that time) Sunnah. Unlike the compactly coded Quran, this vast supplemental knowledge base was orally transmitted across generations. As discussed in Chronology is Key above, during Islam’s second critical intellectual period of approximately 150 to 300 AH, the earliest post-Quranic canonical works, the Sirah and sahih Hadith books, were written after lengthy inquiry and debate about the reliability of the verbal transmissions.22 The latter half of the third century was also when the four major Sunni Muslim schools of thought were institutionalized, alternative schools like Mutazilism were branded as heresies, and the schism between the Sunni and Shia deepened. Subsequently, over a long five centuries, the canonical books of the 3rd Islamic century were further cemented in the 6th through 8th centuries by the erudite efforts of many scholars like al Ghazali (505/1111), al Zamakshari (538/1144), al Jawzi (597/1201), al Qurtubi (671/1273), ibn Taymiyyah (728/1328), ibn Kathir (774/1373) etc.

Thought Police

It is important to realize that these post-Quranic canonical books, the Sirah and sahih Hadith, were written in an era where there was no freedom of expression, or the equivalent of modern academic tenure, to protect the scholar’s livelihood. Unlike our ‘Amazon age’ where dozens of books are published daily, very few books were published in that era. Throughout history, books of ideology have attracted the attention of both the intellectuals and the governing elite; the latter would have scrutinized books or any opinion as a potential threat to the state’s view of the world. For example, the later Umayyad rulers, who predated the compilation of the Sirah and Hadith books, executed theologians for simply stating what is self evident to most Muslims today: that Allah’s authority is absolute and the Caliph is subordinate to it.23 Also, given the game of thrones underway, the license to publish, when granted by one short-lived ruler, did not necessarily extend to the next.

Persecuted or Protected? – Political interference in theological disputes was common, and leading Imams were either persecuted or had police protection for parts of their careers. They include some time spent in prison for all the four founders of the leading Sunni madhabs — Abu Hanifa (d. 150/767), Malik ibn Anas (d. 179/795), as-Shafi’i (d. 204/820), Ibn Hanbal (d. 241/855). Some died in prison, such as Abu Hanifa and Nuaim bin Hammad (d. 228/843). The Umayyads (41/661-132/750) executed Qadari theologians.24 This is a partial list, it is likely there were more within the Sunni or proto-Sunni sphere, i.e. without delving into Sunni-Shi’i polemics. Persecution continued well beyond the 3rd century and afflicted even the Imams that Traditionalists respect most today, such as Ibn Taymiyya (d. 728/1328) and his student al-Jawziyyah (d. 751/1350).

The opposite occurred too – rulers offered police protection to scholars who were physically threatened. For example, al-Tabari, the master historian, was stoned and regularly threatened by his Hanbali opponents and was under frequent police protection.25 This continues into the modern era, with recent examples being the Saudi state’s arrest and defrocking of Saudi scholar Sayyid Muhammad al-Maliki (d. 2004)26 and the imprisonment of Shk. Salman Alodah who faces the death penalty.27 As rulers changed, so did the allegiance of the scholars. As a contemporary critic notes, “it is binding upon the believer to love the ruler, defend him, and not insult him. Each fatwa or statement has been versatile and able to fit changes in the political hierarchy”.28

The big question is if and how did that political interference influence their scholarship? Which other Imams with valuable views were cowed or censored? For those who cite a scholar’s imprisonment as proof of his incorruptibility, how do we know that the Imam’s subsequent license to publish was not a capitulation, either to the same or to a successor ruler? It is highly unlikely that such state interference did not adversely impact the evolution of the religious community, and the post-Quranic books, that Traditional Muslims continue to extensively rely on?

Those who defend the scholastic integrity of the Tradition assert that the rulers did not interfere. We disagree; the authors of the Sirah and Hadith books were public intellectuals; people of such prominence would not have been able to publish works of any import without the ruler’s acquiescence, if not patronage. Further, since there were no productivity tools, such as a word processor or printing press, publishing a book was a laborious task spanning years, during which time the author’s living expenses were probably paid, either directly or indirectly, by the largesse of the ruler or a state-friendly benefactor. Even in cases where the scholars were independently wealthy, as in the case of Tabari, we have to keep in mind that private property rights in that era were often an extension of the ruler’s favor. Therefore, unlike the Quran that was a direct revelation of uncontested opinion, it should not surprise us if post-Quranic books were skewed by opinionated debate and attendant political interference. The modern notions of freedom of expression and academic tenure, critical ingredients in scholarship, were missing in that authoritarian era.

House of Wisdom

An enormous conflict between religious and political authorities occurred during the reign of Caliph al-Mamun. The story begins with al-Mamun’s signature achievement. He was the key catalyst to the golden age of science and reason, in keeping with his personal inclinations – he is noted to have “devoted himself to the reading and intense study of ancient books, and attained expertise understanding them”.29 His grandfather, Caliph Harun al-Rashid, had established a small think tank called the House of Wisdom, Dar al Hikma, which some scholars believe was merely a relocation of an academy located in Jundishapur after the fall of the Sassanian empire.30 Regardless of its origins, al-Mamun funded it generously to attract the best and brightest scholars of the day from near and afar, akin to an early Oxford or Harvard. This spawned (or extended) a Translation Movement where scholarly works from other cultures like Greece and India were translated into Arabic and further developed. The impact of this was an unprecedented knowledge revolution. Before long numerous scientific innovations resulted ushering in a golden age of Islamic science at a time when most of Europe lived in darkness and despair (although multiple parts of Asia, especially East Asia, were developmentally ahead too). The knowledge revolution coincided with a power struggle between two types of intellectualism.

The Battle for ‘Open Reason’

In a typical Sunday school curriculum, Muslim kids hear about many historical battles that the Prophet’s followers were subjected to (to avoid genocide and in defense of their natural right to practice their faith). A under-appreciated yet pivotal historical battle was not a military one but an intellectual one, between the proponents of ‘open reason’ (our terminology) and the Traditionalists; the latter practiced a form of ‘closed reason’. It occurred in the ninth century, about two hundred years after the Prophet ﷺ.

Those favoring what we call ‘open reason’ were the Mutazilites. They wanted to interpret the Quran with the full faculty of human reason — while accepting the infallibility of the Quran, they wanted to understand it more deeply using all modes of reason, including those learnt from other cultures, especially the Greek philosophers. The Traditionalists limited themselves to a narrower form of reason, or ‘closed reason’. They were led most prominently by Imam ibn Hanbal (d. 241/855) and later by Imam al-Ash’ari (d. 936 CE). They averred that open reason goes beyond the narrow mandate inherited from the Prophet ﷺ and gravely risks subverting the true message of God/Allah ﷻ. They thought a simplistic and literalist confinement to the four-sided sandbox of Quran-Hadith-Sirah-Sunnah was the only pure way to comply with His directives. Ironically, a half century later al-Ash’ari, a former Mutazilite switched over to align more closely with Imam Hanbal’s Traditionalist view, and most Sunni’s today are his intellectual descendents, or Ash’arties. He then employed the Mutazilite reasoning techniques to bolster his newfound views, albeit with a narrow boxed-in perspective, as we discuss later.

Power of the Preacher – There were many deep and abstruse philosophical debates between the Mutazilite and A’sharite camps, often related to resolving the free will versus predestination conundrum that many religions have struggled with.31 As a result a schism developed in the ulama, which worried al-Mamun. He feared a theological rupture would eventually manifest into social instability, since popular preachers could draw crowds numbering the thousands.32 Worse, if left unchecked, the popular preachers could eventually trigger another war in his fractious empire, a lesson he had learnt from his study of a political strategy text, the Testament of Ardashir, authored by the founder of the Sassanian dynasty.33

Imposing Rationalism – After examining the issues, and consistent with his progressive mission to advance science and technology through the prolific Translation Movement at Dar Al Hikma, he sided with the rationalist Mutazilites. The traditionalist Ash’arites were strident in their views and continued to discredit the rationalists. Tired of the debilitating and dangerous debate, al-Mamum did what many an emperor has often done — govern with a heavy hand. He launched an inquisition, called the Mihna, where he summoned the Asharite ulema and issued an ultimatum — switch to the rationalist view or face severe consequences. All leading Imams capitulated except Imam Hanbal, the founder of what later become known as the Hanbali madhab. Toward the very end of his reign (four months prior to his death) Caliph al-Mamun had Imam Hanbal jailed, removing the last remaining obstacle to the acceptance of open reason as the primary basis for interpreting revelation. The age of reason and the scientific prowess of the House of Wisdom was now fully in play with prolific results that we celebrate to this day.

The Battle for ‘Closed Reason’

The tide of open reason did not outlast al-Mamun too long. Although Imam Hanbal was muzzled, the reactionary Hanbali school of thought continued to pull people into its orbit given the directness and simplicity if its boxed-in literalist message. When al-Mamun died in 218/833, his next two successors, al-Mutasim (d. 227/842) and al-Watiq (d. 232/847), continued to carry the torch of open reason. It is widely believed that al-Mutasim ups the pressure on Imam Hanbal and has him flogged.

Impious Khalifa Turns to Hardline Imam – Now we come to a critical juncture. The tenth Abbasid Caliph, al-Mutawakkil (d. 247/861), although a harsh authoritarian like most Caliphs of that age, was pious in a ritualistic sense, notwithstanding a huge harem.34 His reputation for piety is further undermined by his extravagant spending on nearly two dozen palaces, and was known to be a heavy drinker.35 It is not clear whether it was some latter-day turn to piety, or intellectual reductionism, or a desire for greater political control over a fractious empire that led him to reverse al-Mamun’s theological preferences. He strongly opted for the literalist or Traditionalist approach of Imam Hanbal, and gradually ended the Mihna over a five-year period, 232/847 to 237/852. He freed Imam Hanbal, and rehabilitated him. This validated the Hanbali madhab, the last school to crystallize in what is traditionally accepted as the major four schools of theology within Sunni Islam. He then reallocated state resources away from research and learning toward building great mosques of symbolic value. As a result of the defunding of the House of Wisdom, the canonization of recently published books, and other sociopolitical factors, a slow process of intellectual and technological decline resulted.

Reason Circumscribed – Later, a highly constrained or boxed-in form of ‘closed reason’ was then employed by Imam al-Ash’ari, the famous founder of what we today call Sunnism. As noted earlier, he was a Mutazilite for an extended period before flipping over to Imam Hanbal’s side, and thereafter used sophisticated argumentation to build up the Hanbali view to compete with the Mutazili view. With the strong support of the state, he was able to create a coalition of the many opposing groups which resulted in what we now call the Sunni school, ahl-us-Sunnah-wa-al-Jamaah. This is the coalition of people who follow the Sunnah, as defined by the four popular schools (madhabs) that substantially, but not entirely, coalesced at that time – Hanafi, Malik, Shafii and Hanbali. The other major group of people who did not subscribe to the al-Ash’ari doctrine became what we today call the Shia, i.e. those of the party of Ali.

Reason Lives On – Finally, it is important to note that the common perception that the role of reason ended after the 3rd c. AH / 9th c. CE, is inaccurate. Reason continued to flourish, and great Imams like al Ghazzali and Ibn Sina continued to extensively employ it. However, the cult of certitude that developed around canonized Hadith books of the 3rd/9th century (by Imams Bukhari, Muslim etc.) severely constrained the outcomes of later intellectuals since they were boxed-in by the boundaries of Quran-Hadith-Sirah-Sunnah. Perhaps this might have been one of the culprits, but not the only one, for the slow decline that descended upon the Muslim world over the next half millennium. It is tempting to blame the ‘closed reason’ approach for driving the decline of the Muslim world, but that would be too simplistic an explanation for a complex phenomenon. We should be mindful that most empires or societies have failed to retain their vitality for more than a half millennium, if that, especially in the face of major external pressures, as were generated by the Mongol invasions of the 13th c. CE.

Prophetic Medicine, anyone? Ironically, today’s proponents of ‘closed reason’ prefer ‘open reason’ when it comes to the field of medicine. Much of modern medicine has its roots in the Greek system of thought which was adapted to the medical field by Galen (d. 216 CE). The Muslims translated Galen’s works into Arabic and extended it, resulting in substantial new work of Hawi by al-Razi (d. 320/932) and Qanun by Ibn Sina (d. 428/1037). In later centuries, the proponents of ‘closed reason’ tried to create an alternative system of medicine that rejected Galen’s Greek inputs and was entire based on the Quran and Hadith, called Prophetic Medicine or tibb al-nabawi.36 Although now defunct, had it survived, very few Traditionalists might have the courage to rely on it, assuming the alternative of strongly-reasoned Western medicine is available and affordable, although a person of great faith is encouraged to do so. “We have tried the Prophetic cures and found that they are more powerful than any type of regular medicine. Further, this a fact that comparing the Prophetic medicines to the medicines that doctors prescribe is just like comparing regular medicine to folk medicine”, said a leading Imam some seven centuries ago.37

Impact of Canonization

As noted earlier, canonization of post-Quranic books lead to the cult of certitude, which might have had the unintended consequence of undermining the ethical and material progress of the ummah.

Constructing Authenticity

The revelation of the Quran sparked a massive enlightenment resulting in great social strides by seventh century Arab society. The Quran injected the light of reason and promoted human rights to a degree that was centuries ahead of that era’s and that region’s norms (although, to be fair, in other regions and prior eras, sophisticated moral ideas had flourished for varying durations). Given Muslims’ reverence for the Quran, one would expect this forward momentum would continue indefinitely, but it did not. Why?

How is it that just a few centuries later the progressive ethos of the religion was replaced by a narrow and reactionary ideology? Early Muslims had varied interpretations of the Quran and the Prophet’s life, and there was no consensus on it. There were very few books in this era and, other than the Quran, and there were no books that were universally agreed upon as factual or definitive. The diversity of opinion resulted in many debates, which would over time have possibly resulted in higher orders of reason emerging to resolve the intellectual tensions. But instead the community’s leaders converged around a small and widely accepted set of facts that were cemented in canonized books that remain widely used today.

Although the isnad method in Hadith studies is procedurally sophisticated and practiced by brilliant scholars, it is inherently limited by the lack of any surviving written Hadith works concurrent with the Prophetic period or even until more than a century later. Instead, early Muslims relied on the same mechanisms of knowledge transfer as most other societies of that era, ‘oral transmission’ and the ‘living tradition’. To the degree that post-Quranic written manuscripts from the second century exist, such as the Sirah books, we have to question the integrity of their text, especially since they did not go through a formal, albeit fallible, isnad verification process.

Finally, to the degree that books were compiled in the spheres of Hadith and Sirah, initially only a small number of copies existed in manuscript form and widespread dissemination was delayed due to the late advent of the printing press in the Muslim world, as detailed in Tragic Errors. As noted by one scholar, there exist “the inevitable pitfalls of a manuscript culture: the mediation of teachers and scribes in the transmission of a text creates countless openings for both accidental mistakes and intentional modifications that may alter the text and thereby obscure the original authorial intention”.38 Of course, this does not apply to the holy Quran due to the tradition of rote memorization and wide transmission, which forestalled any transmissions errors.

The narrowing of the Muslim mind began with the publication of the Sirah books and the canonization of the Sahih Hadith, both completed under the approval of the authoritarian Caliphs. All religious knowledge that was outside the Quran was at first constructed and canonized, then socialized through madarasas, schools of teaching, and ijazas, licenses to teach. Given the hierarchical nature of governance, and the narrow and harsh policies during the reign of al-Mutawakkil, these books took on an aura of being the ultimate authority and a prerequisite for interpretation of the Quran. As a result, any scholarship that deviated too far from the orthodoxy, as expressed in the selected Sirah and Hadith books, came under fire and was hastily suppressed or gradually withered away. This cult of authenticity of post-Quranic books cemented over the centuries and is now an integral part of a Traditional Muslim’s faith.

Cultivating Certitude

The strong assumption of authenticity of the textual-Sunnah begets an Imam’s air of certitude. Ask your local Imam any question about rituals, morality, history or whatever topic. You will receive an answer filled with certitude about what the rules, expectations, historical facts are, buttressed with quotes from the Quran or Sahih Hadith or anecdotes from the Sirah. The answers are projected with great certitude, to offset the uncertainty that bedevils most of our lives.

For all but the most fortunate, our lives are tenuous and filled with vicissitudes. If we are young, we don’t know if we will find a decent job, where will we live, who we will marry, etc. If we are middle aged, we don’t know whether our job will continue to sustain our lifestyle, why our child is so ill, whether our kids will lead good lives eventually, if our health will last, how long we will live, etc.

Many of us need to lighten this burden of uncertainty, and faith in a higher transcendent power facilitates that. The discomfort of uncertainty needs to be salved. The Imam provides you with psychological relief from the pressures of the present by combining three approaches: a clear description of the past, a vivid preview of the post-life future, the akhirat, and a vector to power you through your worldly trials and tribulations. By trusting our Imam we effectively create a cocoon of certitude, nesting our fears and aspirations inside layers of ancient wisdom.

So, a regular Imam does not have the luxury of vocalizing his intellectual tension, even when he has any. Unlike a true scholar who sees academic opportunity in such tension, the Imam must supply a faux certainty even where isn’t, that is part of his job description. There is nothing wrong with this manner of ministry if it is based on sources that are absolutely authentic. But, unfortunately, beyond the axiomatic truth of the Quran, there are deeply troubling questions of authenticity in post-Quranic sources of Islamic knowledge. These issues deserve reasoned debate but which are being shunted by this popular cult of certitude.

Is Mecca = Becca?

Although we believe that Mecca and Becca are the same town, it is worth examining the contrarian argument. The Quran cites only a few locations, of which two are Bakkah (Becca) and Makkah (Mecca). Since Bakkah is not featured in the subsequent Sirah, Hadith or other books, it presents a mystery.

Makkan narrative: the Traditionalist ulama strongly claim:

1) Bakkah is the old name for Makkah, similar to Yathrib for Medina.

2) For the first 13 of 23 years of the Prophetic period, Muslims prayed toward Jerusalem.

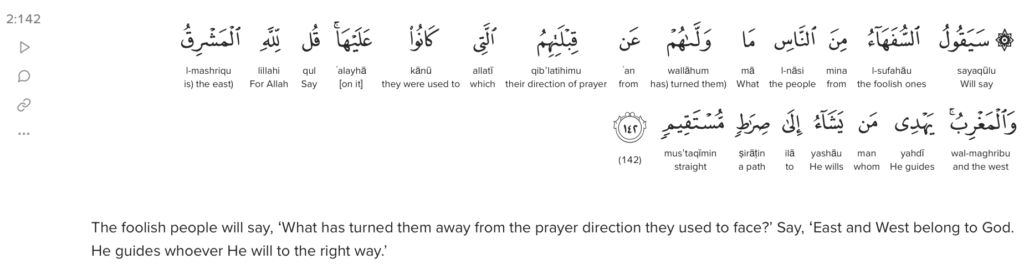

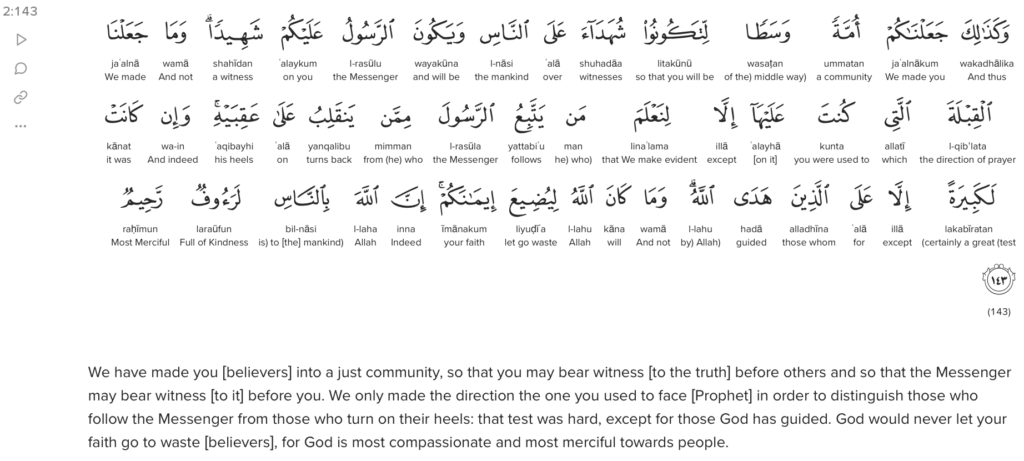

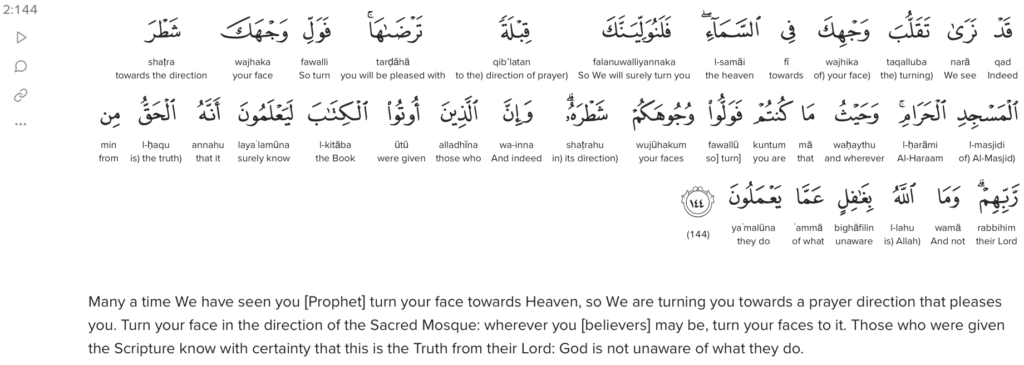

3) upon revelation of 2:142-144, in the year 2 AH, the Prophet ﷺ switched prayer direction to Makkah.

Bakkan narrative – some academics, and most Quranists, believe:

1) the Kaaba was initially not located in Makkah (Mecca) but in Bakkah (Becca), somewhere near Jerusalem.

2) the Bakkah in the Quran (3:96) is the same as the Bakka valley in the Hebrew Bible (Psalm 84:6).

3) 2:142 confirms that the Prophet’s correct prayer direction is Jerusalem.

4) 2:143 criticizes some disloyal Muslims for praying to the pagan gods in the Kaaba.

5) 2:144 corrects the prayer back toward the original direction of Jerusalem.

6) Mecca was never a significant city prior to the 8th century CE since it does not appear on any maps or trade routes until a century after the Prophet ﷺ, and its remote, interior location is an unlikely location for a trade hub.

7) Multiple kaaba once existed, since cube shaped stone structures were a religious object for the Nabateans in North Arabia.

8) Some Muslim ruler erased memory of Bakkah near Jerusalem and falsely equated it with the remote southern town of Makkah. This was perhaps done to consolidate power after the North-South civil war between rival caliphates of Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan (d. 705 CE), a Medinan who ruled from Damascus, and Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr (d. 692 CE) in Bakkah or Makkah. The former won conclusively and the version of truth that prevailed was established by his successors.

9) in 72 AH / 691 CE the triumphant ruler, Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan, builds the magnificent Dome of the Rock, the masjid al-Aqsa, and inscribes it with holy proclamations (as an aside, which surprisingly differ a bit from the extant Quranic text). If prayer had changed away from Jerusalem prior to 691 CE, why invest that much resource in an abandoned direction? But the counter to this counterargument is if they were still praying toward Jerusalem in 691, when and why did they later change direction toward Makkah? Was it during or after the third fitna in 126-132 AH / 744-750 CE, which would have been a very late switch, which is feasible but unlikely? Unless the hypothesis is that one of the rulers altered prayer direction to consolidate north and south Arabia, i.e. boost Jerusalem with a grand mosque while shifting prayer toward Makkah, thus pleasing both warring factions. We run the risk of piling conjecture upon conjecture.

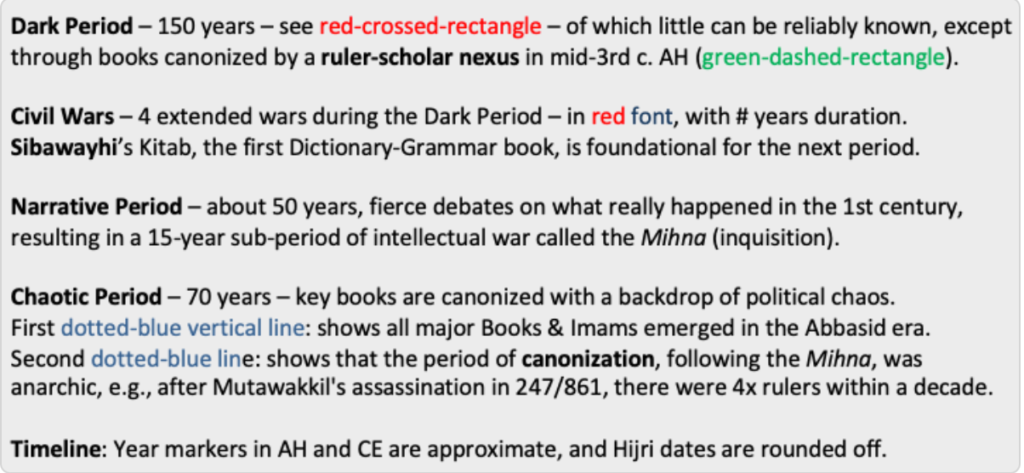

Although verse 3:96 does not explicitly equate Bakkah with Makkah, some translators attempt to do so, as shown in the figure below. Regardless, all Traditionalist ulama, of all sects, equate Bakkah with Makkah. From Quran.com:

Verses 2:142-144 are ambiguously worded and can be interpreted bivalently. The figure below presents the Abdel Haleem translation, which is valued by most secular scholars. A review of other leading translators like The Study Quran, Saheeh, Taqi Usmani etc., results in similar observations. From Quran.com:

How did the Makkan narrative come to be the mainstream view? The first extant biography was written about 200 years after the Prophet ﷺ, in a chaotic game of thrones era, by Ibn Hisham (d. 218/833), about 80 years after the violent Abbasid revolution. As noted earlier, it is a redaction of the pivotal first comprehensive biography written by Ibn Ishaq in 760 CE, in the first decade of Abbasid rule, one which is mysteriously lost. When Hisham’s book is amplified by the sahihayn of Bukhari (d. 256/870) and Muslim (d. 261/875), the Makkan narrative is canonized for posterity.

BioIslam’s stance: It is not possible to now know for certain which interpretation of 2:142-144 is more correct, hence we must be careful not to be brashly revisionist. Since there are zero facts on ground to validate the Bakkan narrative, and especially since no scholar of either the Quran or Hebrew Bible has found solid evidence for an alternate location of Bakkah, we must continue to subscribe to the Traditionalist Makkan view. However, even if the Bakkan narrative is validated by future archeological or other discoveries, BioIslam’s views are unperturbed since it is evidence-based and not reliant on a cult of certitude. However, the probability of such revolutionary evidence emerging is low.

When You Don’t Know

Why pretend to know what we don’t? Although I do not impugn the motives of humble Imams or any dedicated scholar, I suspect the best answer, more often than not, should be, “we don’t really know for sure, so let’s refocus on what we do know”. Indeed, in almost all historical controversies, including the biggest one (i.e. who should have led the community after the Prophet ﷺ passed away, the root cause of early sectarianism), that might well be the best answer. Imam Malik, the founder of a leading madhab or school of thought, said the best shield of a scholar is to say, “I don’t know”. When was the last time you heard your Imam say that?

Amongst practicing-Muslim scholars, with the exception of very few bold and brilliant ones who enjoy academic freedom in the open societies of the West, very few vigorously challenge the Traditional sources. Those that have tried were at first ignored and later demonized, such as Sayyid Ahmed Khan, Fazlur Rahman and Nasr Abu Zayd.39 A pro-science person further observes that the Traditionalist approach of certitude has failed to solve the aforementioned Big Five problems. Unfortunately, beyond the axiomatically infallible Quran, reliable source materials for the first century of Islam simply do not exist. We wish they did.

Ghayb – Beyond Truth

How far can we pursue the truth? In BioIslam, beyond the aforementioned axioms, there are no certainties, only probabilities and possibilities. There are two areas in which BioIslam does not dispute Traditional Islam is the aural-Sunnah and the ghayb. The former has already been discussed. The latter is the world of the unseen, the known unknown. There are many references to angels and jinn in the Quran and the Traditional views on the ghayb are not incompatible with BioIslam. Traditionalists are obligated to believe in jinn as a reality not a metaphor.40 However, on matters of the ghayb, BioIslam acknowledges that there is much we do not know, and cannot know, while on this earth. For example, even though many types of jinn are identified, there is limited knowledge of their role.41 All Traditional Muslims have no choice but to remain open to the possibility they are a physical reality, even if such belief does not play an active role in daily life.42 The elaborate role assigned to angels in Islamic cosmology could well be real, and we should not rush to rule it out as purely metaphorical.43

How can a pro-science person reconcile such supernatural speculations with the sturdy naturalism of science? To remain open to the reality of the ghayb is a leap of faith, but not that much greater than the leap of panpsychism, the belief held by some modern physicists and philosophers, that inanimate objects can have consciousness.44 However, BioMuslims stop short of asserting that invisible beings such as jinn and angels surely exist, versus some credible scientists who claim that invisible creatures might already be living amongst us,45 possibly in a shadow biosphere.46 Additional discussion of the ghayb continues in ‘Processing the Paranormal’ in Waiting for Isa/Jesus.

For those who need an extended warm bath of certitude, to soothe the stressful uncertainty of their earthly life, and for those whom critical thought is viewed as more of a burden than a blessing, BioIslam will hold less appeal than Traditional Islam.

Footnotes

- Since the year of Hijra was about 10 years before the death of the Prophet ﷺ the year as stated in AH can be approximated to mean after the Prophet ﷺ, since our analysis focuses on the big picture of the first three or so centuries, and being off by a decade is not consequential.

- Together with Bukhari and Muslim, these six authors constitute the Sahih Sittah collection – ibn Maja (d. 273/887), Abu Dawood (d.275/889), Tirmidhi (d. 279/892) and an-Nasai (d. 303/915).

- We use the simplifying assumption that the books are deemed completed upon the death of the author. However, in some cases, it was their students who may have written the books for them (a la lecture notes) and may not have completed them until after their teacher’s death. It could be argued that the pivotal-book period began a couple of decades earlier during Imam Malik’s time, but we have chosen to begin with Imam Shafi’i since his impact on our present-day concerns has been far greater, and since Shafi’i extensively credits his teacher Malik.

- Fiqh is jurisprudence, an attempt to translate the divine requirements of human conduct, as given to us by the Quran and the Sunnah, into everyday practice.

- Ahmed El Shamsy, The Canonization of Islamic Law, 4.

- Haider, Najam, Contesting Intoxication: Early Juristic Debates over the Lawfulness of Alcoholic Beverages, Islamic Law and Society, 2013. Also, K. Kueny, Rhetoric of Sobriety. Also, Chapter 4, Wine, Coffee and Holy Law in Ralph Hattox, Coffee and Coffeehouses.

- Taha Alalwani, Reviving the Balance, 98.

- Abdel Haleem, in The Cambridge Companion to Classical Islamic Theology, edited by Tim Winter (aka Shaykh Abdal Hakim Murad), 23.

- ibid

- The sahih movement appears to have extended for a further half century, and a massive hadith collection by al-Busti is considered to be the final installment, says JAC Brown, in Hadith, 2nd ed., 34.

- Spanning over 4,000 miles in width, which is wider than the present day United States, it hosted not just Arabs and Persians, but also significant numbers of Armenians, Berbers, Copts, Greeks, Georgians, Turks and others (using modern ethnic nomenclature).

- Michael Cooperson, al-Ma’mun, 8.

- The Umayyad empire at its peak ruled about 8% of the world’s land area, and was an exponentially larger entity than the Hijaz region, over which the Prophet ﷺ presided.

- Paper was discovered by the Abbasids during an early encounter with the Chinese in 134/751 at the Battle of Talas in modern Kyrghystan.

- Shahab Ahmed, Before Orthodoxy, 27, and Alfred Guillame, The Life of Muhammad, A Translation of Ibn Ishaq’s Sirat Rasul Allah, xiii.

- JAC Brown, Hadith, 2nd ed., 88-89.

- Najam Haider, The origins of the Shia, 24.

- For example, the adoption of the Nicene Creed (or later Chalcedonian) version of Christianity as the official state religion of the Roman Empire in the 4th c. CE

- Talal Asad, The Idea Of An Anthropology Of Islam, 1986, Georgetown Univ.

- For example, in Christianity, three critical intellectual periods include the compilation of the New Testament in the 1st c. CE, the establishment of the Nicene creed in the 4th c. CE, which affirmed trinitarianism and cemented the Catholic church, and the Protestant reform of the 16th c. CE.

- The rasm refers to the consonantal form of the initial Quran; the final version, with vowels, which we use today, did not appear until many decades later.

- An exception is the highly regarded Muwatta of Imam Malik (d. 179/785), but its importance was superseded by the canonical books of the 3rd c. AH.

- Ira Lapidus, A History of Islamic Societies, 102-3.

- ibid, 102.

- Notes to al-Tabari’s History of the Prophets and Kings, by translator F. Rosenthal, vol. 1, 73,74,77,78.

- sunnah.org/history/Scholars/honoring_as_sayyid_Alawi.htm

- Shk. Yasir Qadhi, a leading Traditionalist scholar, has been particularly vocal in his defense of Shk. Salman Alodah. For context, see nytimes.com/2019/02/13/opinion/saudi-arabia-judiciary.html

- Abdullah Alaoudh, State-Sponsored Fatwas in Saudi Arabia, carnegieendowment.org/sada/75971

- Michael Cooperson, al-Ma’mun, quoting al-Masudi, 32.

- Ira Lapidus, A History of Islamic Societies, 109.

- One such debate was on whether the Quran was created or coeternal with Allah ﷻ. Another was whether a Muslim who committed a major sin should continue to be classified as a Muslim.

- Michael Cooperson, Al-Ma’mun, notes crowds numbering in the thousands, 82.

- Michael Cooperson, al-Ma’mun, notes he studied the Testament of Ardashir, 33. This appears to be a book written around 250 BCE, perhaps similar to Kautilya’s Arthashastra in India, written around 300 BCE, or Machiavelli’s The Prince in Italy, written around 1530 CE. It was translated into Arabic and cited by many scholars in Mamun’s era.

- Kecia Ali, in Marriage and Slavery in Early Islam, p. 22, notes that, according to Traditional sources, his harem had between 4,000 to 12,000 women, of which a small fraction were concubines, which suggests at least dozens if not a hundred-plus concubines.

- Hugh Kennedy, When Baghdad Ruled the World, relies on al-Masudi for this information. 148-49, 165.

- Albert Hourani, History of the Arab People, 203.

- Imam al-Jawziyyah, Healing with the Medicine of the Prophet, translated by Jalal Abual Rub, 16.

- Ahmed El Shamsy, Al-Shafii’s Written Corpus: A Source-Critical Study, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 132.2, 2012.

- Sayyid Ahmad Khan (d. 1898), the eminent founder of Aligarh Muslim University, was viewed very negatively by Indian ulama because he questioned certain details of the Sirah and Hadith. Fazlur Rahman (d. 1988), a respected scholar at the University of Chicago, was pushed out of Pakistan by the ulama for views they considered heretical. Nasr Abu Zayd (d. 2010), a scholar at Cairo University, was declared an apostate by fellow ulama in 1995 for advocating a Quranic interpretation that the ulama judged as heretical.

- Shk. Wahid Bali, How to Protect Yourself from Jinn, documents strong support for the the concepts of Jinn in the Quran and Sunnah. Dr. Khaleel Ameen, The Jinn and Human Sickness, discusses the role of Jinn in causing illness, both physical and psychological, and how to treat them, including the use of ruqya, formulas to expel jinns if a human is possessed. Both books were sourced from Kalamullah.com

- The types of jinn are hinn, al-ghoul, jann, marid, ifrit, shiqq, nasnas, palis, silat, and shaitaan.

- Amira El Zein, Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn, comprehensively discusses the large and recurring role of Jinn in Islamic cosmology.

- Shk. Hisham Kabbani in an inspiring book, whether or not it is literally true, Angels Unveiled, says every rain drop is brought down by an angel and it takes seven angels to help a leaf grow.

- Philip Goff, a respected philosopher, is a strong proponent of consciousness in the inanimate world, in The Case for Panpsychism, Philosophy Now, Aug/Sep. 2017. Also, Giulio Tononi, the leading theorist of consciousness, has a sophisticated mathematical model that allows for a non-zero level of consciousness in any inanimate object that integrates information, such as an electron, a silicon transistor or an organic molecule. Others who accommodate such beliefs include David Chalmers, a pioneering philosopher in the field of consciousness, Christof Koch, a leading biophysicist, and Max Tegmark, a prominent physicist.

- Britain’s first astronaut, and a credentialed chemist, Helen Sharman, strongly believes in aliens and says, “It’s possible they’re here right now and we simply can’t see them”, The Guardian, 05 Jan 2020.

- Carol Cleland, a philosopher, asks whether contemporary Earth might be host to ‘shadow microbes’ which are undiscovered alternative forms of microbial life, in A Shadow Biosphere, Astrobiology Magazine, Dec. 2006.