1st c. AH – No Dictionary/Grammar

The Dictionary/Grammar Problem immediately results in a Translation Problem – how to translate phrases like ghayril maghdoobi alayhim or words like auliya, mawla, daraba, mutawaffika, ahl al dhikr, and potentially many more. Many of these words are the root cause of our current interpretive conflicts. This begs the question – how was the first Arabic dictionary or grammar book constructed? The goal of this analysis is not to arrive at a better dictionary/grammar book, but to realize there were significant problems in the dictionary/grammar making process, which undermines the certitude of the Traditionalists. This problem cannot be undone (and afflicts the books of other faith traditions too) — efforts to do so simply replace one dubious meaning with an uncertain alternate. This fundamental constraint on our knowledge suggests that we need to interpret the revelation in a way that minimizes the impact of dubious meaning.

The root cause: the first dictionary/grammar books of Arabic were compiled more than 150 years after the Quran, and after a prolonged process of debate and negotiation. The process of assigning precise meaning to words, and the grammatical rules of sentence construction, were not fully documented until much later than most Muslims realize. Most importantly, even when it did occur eventually, the early dictionaries did not undergo an extensive formal validation process, unlike the Sahih Hadith a century later. The content of the earliest dictionary and grammar books is likely to have been substantially influenced by post-Quranic developments. Therefore, they are imperfect tools for deciphering the Quran and other post-Quranic documents. Since we do not have access to any Arabic dictionaries or grammar books (or any complete books for that matter) from the pre-Quranic era, we are stuck with this problem and must be sensitive to the limits it places on interpreting the Quran (or the texts of any ancient religion for that matter).

The Muslim world went through massive geographic, and consequently linguistic, expansion in its first century. The sudden and stunning Arab conquest of Persia around 650 CE had a profound impact on the culture and languages of both regions, but exactly how is buried in obscurity.1 Although it was the Arabs who conquered the Persians in a territorial sense, the opposite might be said in a social or intellectual sense because “it is a remarkable fact that, with few exceptions, most Muslim scholars both in the religious and intellectual sciences have been non-Arabs.”2 Also it is likely that the changes that occurred during obscurity were asymmetric — was it only the Arab conquerors who imposed elements of their language onto the conquered Persians, or did Arabic itself change substantially after it came into contact with the language of a sophisticated ancient civilization? The Persian script was entirely replaced by the Arabic one, but how much flowed in the reverse direction?

There was enough influence of foreign languages on Arabic to spark a debate on preserving the ‘true’ Arabic. The ulama claim Arabic is God’s chosen language, a pure and clear tongue, and was not impacted by Persian influence, but is this realistic or merely a pious defense? One scholar says, “Soon urban forms of spoken Arabic were felt to be more open to ‘corruption’ than the language of bedouin tribes. The rift between the language of the city-dwellers and Arab nomadic or semi-nomadic tribes was to make a lasting impact on the history of Arabic dialects.” He goes on to say, “In areas outside the strictly legal and religious field, scholarly Arabic from the second/eight century onwards underwent a massive influx of foreign words, loanwords and loan translations.”3 What was the impact on the religious field? We don’t know for sure, but surely there would have been some influence, especially since it was a long arduous task.4

There was enough concern about the adverse impact of cultural accultration on the Arabic language that some scholars claim that Khalifa Ali gave instructions to start writing the first dictionary and grammar books.5 However, other scholars believe this is a pious fiction and the grammar writing started much later.6 In any case, there was enough concern about Arabic being corrupted by foreign contact7 that at some point, most likely during the time of Sibawayhi (and his teacher Farahidi), an extensive project of philology started. “These linguistic efforts persisted for more than a century and produced what we now know as classical Arabic.”8 All the early books in Arabic, most importantly the dictionary and the rule books of grammar, all crucial to interpreting the Quran, were authored primarily by Persian scholars, as we discuss below.

2nd c. AH – Persian Gifts

Not everything about the 1st c. AH is obscure. We know the Persians gifted their Arab overlords with tremendous intellectual capital, especially in the Dictionary/Grammar arena. The Hijazi Arabic of the Quran was a relatively newly formed tongue with primitive scripting abilities. Although the Arabs of that era excelled at poetry, they lagged linguistic leaders in producing prose, judging by the output of the ABC camp – Aristotle, Buddha and Confucius – who preceded Islam by about a millennium. The 7th-century Persians possessed enormous intellectual capital, gradually accumulated over their longstanding empire (est. 550 BC), which benefited from fertile lands, a diverse polyglot population, and extensive interactions with Greece, Rome and India. Thus, the sophisticated Persians were a millennium ahead of the rustic Hijazi Arabs of the 7th century, which makes their swift military demise all the more shocking.

The first Dictionary-cum-Grammar book was called al-Kitab, or simply “the Book”, a generic title since the original lacked one. It was compiled in the second Islamic century by Sibawayhi (d. 174/796), the famous Persian grammarian who built upon the work Kitab al-ayn of his teacher Farahidi (d. 164/786).9 Sibawayhi credits his teacher extensively, but disagrees with him as well.

This occurs over a century before the first tafsir or book of interpretation of the Quran emerges. Therefore it is a pivot point, key to determining the meaning of the Quran. The quest to define language and infer meaning was a long-running project that spanned centuries. “During the pell-mell imperial expansion from the 630s onward, Arab vision had been blurred by the sheer speed of movement… To put this right, scholars turned to those whose lives still revolved around pasture – the bedouin. From the later eight century onward, philologists, lexicographers and ethnologists form the towns descended on the remaining Arabs whose lives were supposedly uncontaminated by urban ways and speech.”10 Thus, the efforts of Sibawayhi and other linguists in the second Islamic century were a mere starting point in the struggle to arrive at a consensus on meaning. “Anyone who doubts the intense, introverted, and navel-gazing centrality of the Arabic language to Arabic thought should reflect on the fact that ‘for the period between 750 to 1500 we know the names of more than 4,000 grammarians’… the ‘grammaratchiks’ monopolized truth, became sole mediators with a text-based God, and began to occupy a place not unlike that of the priesthood in a Christian setting.”11

During Sibawayhi’s time, the second Islamic century, it was not easy to establish the meaning of the Quran, especially given the dynamics of a rapidly changing society in the wake of unprecedented geographical expansion. “Arabic grammatical treatises are full of references to the ma’na or ‘meaning’. By this they refer to the intention of the speaker, but not to the lexical meaning of the words, which was reserved for lexicography.”12 But such inference is likely to have been colored by a culture in flux, a tussle Arabs and Persians, the conqueror and conquered, over establishing the rules of the written Arabic, as we shall discuss next. The linguistic flux was accelerated by inter-marriage, “The chaste Arabic of Medina and even of Mecca began to be invaded by Persianisms from the interloping mother-tongue.”13 The writing system of the Arab’s lagged that of many other civilizations, including the Persians, hence the latter take the lead in writing the dictionary of Arabic and the rules of grammar, which is consistent with the overall Persian dominance of the intellectual sciences in the centuries that immediately followed the Arab conquest.14

Before casting doubt on its integrity, we must acknowledge that Sibawayhi’s substantial effort spans about 1,000 pages. It is a comprehensive dictionary-cum-grammar book, but we sometimes refer to it in shorthand as “dictionary”. “The authority of the Kitab is such that it has been called “the Quran of grammar” and set alongside works of Aristotle and Ptolemy as one of the three most important books ever written.”15 A couple of centuries after Sibawayhi, one scholar praises his lasting contribution by placing it on the “same level with Ptolemy’s Almagest and Aristotle’s Organon maintaining that each of the three book did not leave out any of the truly essential elements to its field.”16 Many later scholars accepted it as the gold standard, and acknowledged it would take a lifetime to master it and its derivative works.17

Meaning-Making Controversy

Despite this high praise for the Kitab, much remains unsettled. According to a leading contemporary and unbiased historian of Islam, “Our field of Near Eastern studies seems generally to be slow to provide us with proper tools and working aids – for example, we still after all these years do not have a good dictionary of Classical Arabic, much less a historical or etymological dictionary of Arabic.”18 Sibawayhi was prolific, yet he came under heavy criticism centuries later by the famous ibn Taymiyya (d. 706/1328) who claimed there were 80 errors in the al-Kitab.19 Contemporary scholars have noted the disadvantage of his Persian roots, “his Arabic was sometimes less than elegant… and the overall organization is not of the highest order.”20

Whether or not these acute criticisms are valid, it does show that eminent figures continued to debate the accuracy of Sibawayhi’s book. Even if his scholarship was impeccable, compiling any seminal work of meaning, especially in an age of socio-political strife, such as that of Sibawayhi’s time, is bound to be rife with controversy because “surface forms of language reflect resolutions of conflicts between competing constraints.”21 So, does the Arabic dictionary we have today reflect the true meaning of the words, as originally utilized to articulate the Quran to the people of the Prophet’s time, or that which the scholars generations later believed? Linguists believe that the meaning of a text lies at a layer below the words that were once used to represent it – the “meaning of a text is not simply found in the mens auctoris but rather in the mens lectoris or, better, in the complex relationship between the text and its readers in their contexts.22

Traditional Muslims are piously taught that the Quranic Arabic is a high classical Arabic. They believe since it is the speech of God/Allah ﷻ it holds the highest literary status and is inimitable. In utter contradiction, Traditional scholars are in consensus that the Quran was revealed in seven ahruf, different forms of the Arabic language, as we discuss in Quran Integrity Debate. Regardless of whether the Quran was revealed in a singular Arabic, which is the belief of BioMuslims, or seven language variants, which is the belief of Traditional Muslims, the Prophet somehow ensured that the people of his time came to clearly comprehend it. It had to be so, to fulfill the promise of “a clear Arabic language” (Q. 26:195), and in keeping with the spirit of “If We had made it a foreign Quran, they would have said, ‘If only its verses were clear! What? Foreign speech to an Arab?’” (Q. 41:44).

The early beginnings of grammar and lexicography began at a time when Bedouin informants were still around and could be consulted, even if they were three or so generations separated from the sahaba. There can be no doubt that the grammarians and lexicographers regarded the Bedouins as the true speakers (fusaha) of Arabic.”23 Another scholar notes, “the structure of the language of the Quran resembled that of the Bedouins’ spoken language, and that both these sources represented the same kind of language”. More surprisingly he says, “The fact that Sibawayhi sometimes holds that a construction in a certain Bedouin dialect is preferable to a corresponding one in the Quran shows that his criteria were purely scientific, and that his judgement was not influenced by any religious considerations.”24

The Bedouin Controversy

Not all scholars agree with the above Bedouin dialect hypothesis. A leading scholar says, “In sum, the orthography of the Qur’an seems to reflect Meccan or Hijazi dialect, yet the text calls itself and is considered by most modern philologists to reflect some form of the ‘arabiyya or poetic formal language. It cannot be both, but how this paradox is to be resolved remains to be seen.”25 Which prompts the question, did the introduction of orthography alter the original, a topic we address below in “The Rasm Non-Problem?”.

Here is one instance of how this rural vs. urban conflict between Bedouins and city-dwellers impacted scholarship: a critique of Sibawayhi’s work was made by the most prominent of his rivals, by al-Mubarrad. He subsequently retracted more than half of his criticisms possibly “motivated by an attempt on his part to emphasize the group he himself identified with, the grammarians of Basra.”26 In this Sibawayhi-Mubarrad tussle, which is part of a larger rivalry between the grammarians of Basra and Kufa, a Bedouin arbiter is appointed. Sibawayhi’s rival “wins by bribing some Bedouin to support his position, and Sibawayhi goes off and dies of grief, consoled, some say, by a payment of 10,000 dirhams.”27

“In the story about Sibawayhi and the Bedouin informant, there is already an element of corruption; the stereotype of the Bedouin later became that of a thieving and lying creature whose culture was inferior to the sophisticated sedentary parts of Arab civilization. For the practice of grammar, this meant that the process of standardization had come to a standstill. Since there were no longer living informants to provide fresh information, the corpus of the language was closed, and ‘fieldwork’ could no longer produce reliable results.”28 Note that the first comprehensive tafsir or interpretation of the Quran does not appear until a century after Sibawayhi, by al-Tabari (d. 310/923).

Some of the conflict between grammarians was perhaps wrongly projected onto them by later figures. One scholar believes after Baghdad was established by the Abbasid dynasty, there was intensified rivalry — personal conflict between thought leaders in the older cities of Basra and Kufa (the former is where Sibawayhi resided while writing his book). This conflict was “artificially projected back to the grammarians of the second/eighth century.”29 Another scholar views this as an attempt to “establish a linguistic orthodoxy by contrasting the correct Basran view with the incorrect Kufan.30 If that is true, we must ask whether the opposite could occur too — are there more dubious incidents during the dictionary writing process that were airbrushed out of history — by later scholars who perhaps acted with the pious intention of suppressing the instability at the foundations of Quranic interpretation?

The Shu’ubiyya Controversy

Sibawayhi was also accused by his contemporary critics of having a poor command of Arabic. Perhaps this was because Arab grammarians did not fancy a Persian documenting the rules of the language that they parochially viewed as their remit. Such ethnocentrism was rife at that time. Inspired by the Quran’s implied equality (Q. 49:13) of races and tribes (collectively the shu’ub), the Shu’ubiyya movement by the Persians countered Arab supremacy. This was “not merely a conflict between two schools of literature, nor yet a conflict of political nationalism, but a struggle to determine the destinies of the Islamic culture as a whole.31

According to a leading linguist, Sibawayhi “was certainly a victim of the Shu’ubiyya movement, that short-lived ethnically inspired struggle for cultural supremacy that left the non-Arab Muslims with no choice in the end but to embrace the Arabic language and Arab cultural values, into which they imported as best they could the literature and taste of their original homelands. The movement was in full swing in Sibawayhi’s day, and as a Persian he would always have been conscious of discrimination.32 Although ‘short lived’ in that this specific controversy does not persist into the present day, it lasted until the sixth Islamic century, i.e. well beyond the crucial third-century of canonical Islam.33

Another eminent scholar demonstrates how the Shu’ubiyya controversy impacted the interpretation of the Quran by noting differences in the tafsir commentaries produced by Persian scholars versus scholars of Arabic origin.34 Another respected scholar observes the challenge to Islamic interpretation arising out of this controversy, “But the shu’ubiya sometimes went beyond asserting equality or parity in favor of the superiority of Persian culture, especially literature. Given the religious history of Persia, and the lingering attachment of Persians to Mazdean or sub-Mazdean beliefs, shu’ubiya also implied a challenge to Islam, or at least the form of Islam advanced by the Arabs.35

The big question is — could the Shu’ubiyya controversy have impacted Sibawayhi’s scholarship, contributing to the Dictionary Problem? Since Sibawayhi lived in an obscure period, before the full light of history shined on the Islamic world, we will never know for sure. However, it is likely that it would have impacted it, given the huge geographic and linguistic expansions of the first Islamic century. One scholar believes “Such influence is likely to have been carried into Arabic by the early converts from the conquered territories, many of whom belonged to educated social classes.”36

Preserving Perceived Purity

Traditionalist scholars claim that Persian influence did not alter Arabic in the religious domain, despite leading scholars like Sibawayhi being of Persian origin. Given that Sibawayhi and others were working in the midst of the Shu’ubiyya strife, and that the Arabs themselves had differing dialects in rural and urban areas, it is a bit much to swallow since religion touched every facet of existence, even in mundane matters. Is this claim by the ulama an attempt to signal purity of the Quranic revelation?

A similar debate occurs on whether the language used in the Quran employed words of foreign origin. Some scholars believe the Quran borrowed text from pre-Islamic recitations, an anathema to both Traditional Muslims and BioMuslims. An alternative explanation is that over time foreign words had entered the Bedouin dialects through their interaction with other cultures, an unsurprising diffusion process we see across many cultures. But Traditionalists are loath to accept any foreign connection. One scholar notes, “In pre-Islamic times, the Arabs had taken over a considerable number of words from the surrounding cultures”. He goes on to say, “The oldest commentaries on the Quran, such as the one by Mujahid (d. 104/722), had no qualms in assigning words in the Quran to a foreign origin”. Even the most religious words were loanwords, such as Quran from the Syriac qeryana, salat from the Aramaic slota and masjid from the Nabataen msgd.37

However, by the end of the second Islamic century, “some philologists had started to attack the notion that the Quran could contain foreign loanwords, and attempted to connect the vocabulary of the Quran with a Bedouin etymology”. “Although most Arab lexicographers, such as as-Suyuti (d. 911/1505), continued to assign a foreign origin to many Arabic words, the idea of the purity of the Arabic language remained the prevalent attitude among some Islamic scholars, and attempts by Western scholars to find traces of other languages in the Quran were and still are vehemently rejected.”38 “In view of the many conflicting theories about the emergence of the new type of Arabic, it is hardly possible to refer to an authoritative account.”39

Although it is too late to know for sure what transpired on this back then, BioMuslims are sensitive to the fact that the meaning of words and grammatical structure of early Arabic could well have mutated in the first century or two as a consequence of the profound territorial and cultural changes that occurred.

Long Linguistic Debate

A centuries-long debate persisted on whether Arabic was an eternal language revealed to the first human, the Prophet Adam ﷺ, as the Quran suggests, perhaps metaphorically (Q. 2.31), or did the language organically emerge across generations through social conventions, in the same manner that normal or non-revealed languages do. This can be summarized as the revelationist vs. conventionalist dichotomy, or tawqif al-lugha v. istilah, and our analysis below is based on research by a leading linguist.40

Although this tawqif–istilah debate is steeped in technicalities, it is important to note that it went on for many centuries. Although Sibawayhi (d. 174/796) produced the Kitab, the definitive book on dictionary and grammar, and the next generation of scholars such as as-Shafii (d. 204/820) employed his linguistic rules in their key works such as the Risala, crucial aspects of Sibawayhi’s and Shafii’s linguistic framework were challenged by later scholars. For example, a century later, Ibn Darastawayhi (d. 346/958) disagrees that homonyms and antonyms are a valid part of the language. This profound disagreement “poses the question why a pious figure such as Ibn Darastawayhi should obstinately refuse to recognize linguistic phenomena which al-Shafii previously identified as irrefutable.”

It appears that there was a dialectical process at work between tawqif and istilah. The early scholars started off with a bias toward tawqif, buttressed by sahih Hadith, a position which would later be deemed orthodox, but later generations of grammarians tilted toward istilah in their sincere quest to further the development of the language. This included expanding it to a broader audience, which included accommodating foreign loanwords, since the territorial base of the language expanded beyond the Arabian peninsula to a far-flung empire.

According to ibn Taymiyya (d. 706/1328), a leading Traditionalist scholar and strong critic of istilah, “the first figure to promulgate innovatively the conventionalist (istilah) perspective was the Mutazilite Abu Haashim (d.321/933).” With pushback from orthodox scholars, the debate was rolled back toward tawqif; for example, in the rationalist camp, the Mutazila, the early scholars called for istilah, but later generations settled for tawqif. A parallel dimension to this debate was the notorious tussle between the Traditionalist Asharite and Mutazilite camps on the issue of the createdness of the Quran, which we examined in Historical Truth. The advocates of istilah were intellectually aligned with the early Mutazila, and when the Asharite camp prevailed the rollback from istilah to taqwif gained momentum. Neither camp was operating on ulterior motives, but the proponents of tawqif were pushing for literalism and suppressing metaphorical or figurative readings, while the advocates of istilah were pushing for a more rationalistic approach that is consistent with the secular evolution of all major languages.

In sum, it appears that the linguistic tone was set by the early Traditionalist scholars, and most of the language development was influenced by the tawqif methodology, but hybridized with some istilah.

The Translation Problem

The Dictionary Problem results in the Translation Problem. Before we examine the problem, note that Traditionalists prefer to call a rendering of the Quran in English an ‘interpretation’ rather than ‘translation’ based on their belief that the original intent of Allah ﷻ can only be accessed through Arabic. BioMuslims reject that claim because the Quran says the choice of Arabic as a language for revelation was only incidental. “In verse 12:2, the Quran says, “Indeed, We have sent it down as an Arabic Qur’an that you might understand”. “And if We had made it a non-Arabic Qur’an, they would have said, “Why are its verses not explained in detail [in our language]?” (Q. 41:44). In prior revelations, such as the Old and New Testaments, God spoke in Hebrew and Aramaic, so there is nothing particularly special about Arabic. Perhaps the only language with the elevated status was taught to Prophet Suleiman ﷺ, the language of the birds.41 We therefore use the commonly accepted term ‘translation’ for a direct rendering of God’s words into English.

Which translation? Most translators of the Quran have come from the Traditionalist school. How should we decide which translation is better? There is no easy answer. The answer of the Arab ulama is all translations are inadequate, therefore you should ‘just learn Arabic’. That will only push the problem up a level. How should a native Arabic speaker decide what a word or phrase means? By relying on a dictionary — and now we are back to the Dictionary Problem. So it is prudent to consult the works of multiple scholarly translators, and when there are differences to learn to appreciate the ambiguity rather than rush to the certainty projected by a single translator. At the end of this section, we discuss which translators we rely on.

In fact, the lay native speaker of Arabic is at greater risk of misinterpreting a verse than a non-Arabic speaker, since the latter is more likely to consult multiple scholarly translators. In contrast, the native speaker confidently marches through it with what cognitive psychologists call a ‘fluency illusion’, i.e. the native thinks he/she knows what it means, even if his/her comprehension is at odds with that of an Arabic language scholar. As a leading Arabist notes, “But for non-Arab Muslims the sacred sounds were not enough: they had to look for the larger meaning, the sense, as one inevitably does when one translates. The curious upshot of this is that non-Arab Muslims may in fact understand the message of the Arabic Quran as well as, if not better than, many of their Arab co-religionists.”42

While BioIslam’s multi-translator method is not entirely free of this problem, it is more likely to result in a dilution of errors, versus the reinforcement of errors inherent to a single native-reader approach. This is because the human capacity for language is the result of the interaction of genetic and cultural processes. Since culture is a construction that morphs over time, it is likely that any interpretation of a text will evolve, even without trying. When the text being interpreted is anointed as divine (Quran), or divinely inspired (Hadith), even the most sincere interpreter, one who attempts to absorb the original meaning of the text, is inevitably interpreting it through a linguistic lens that has been colored by centuries-old cultural constructs.

Next, we list examples of the Dictionary Problem results in a Translation Problem.

Sura Fatiha

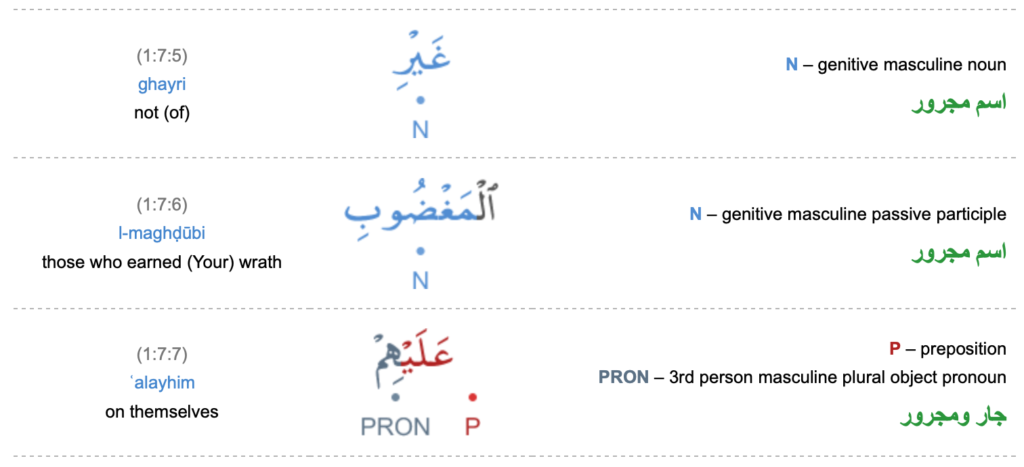

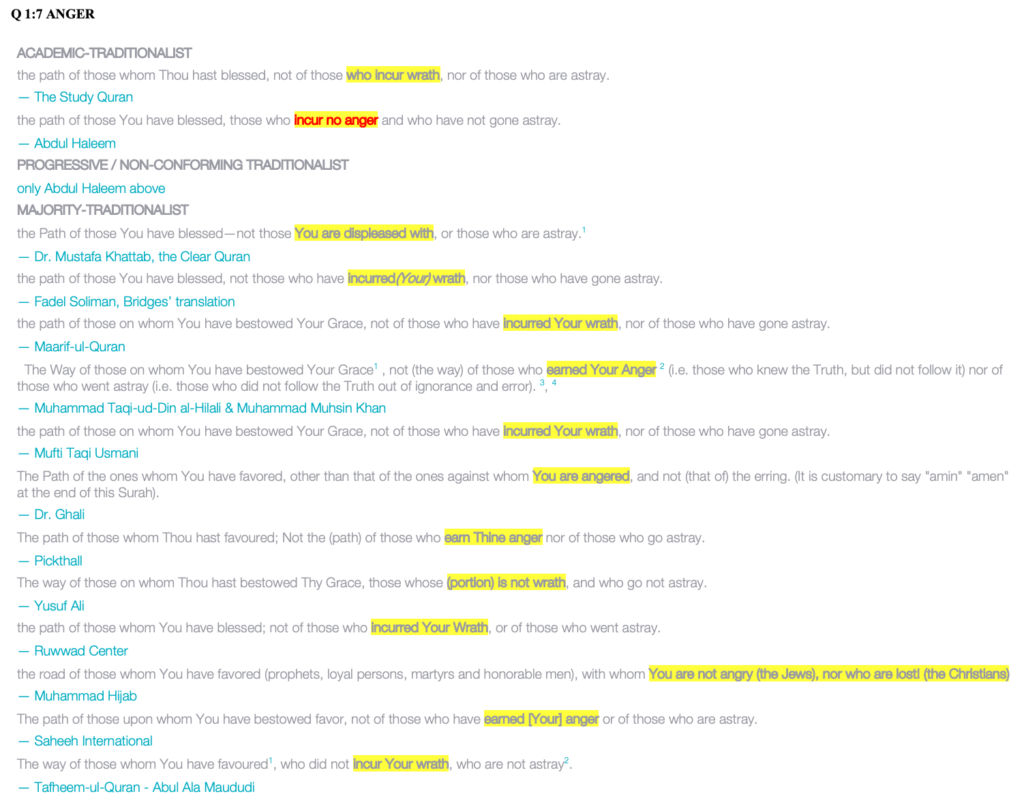

First, the Sura Fatiha poses a surprising grammatical challenge. How to translate verse 1:7, ghayril maghdoobi alayhim? Does the Quran refer to God’s anger or our human anger, an important distinction? There is no consensus — it is translated differently into English across the eight mainstream translations of the Quran. Three popular translators refer to God’s “wrath”, four refer to God’s “anger”, whereas another eminent translator, Abdel Haleem, writes “those who incur no anger” and explains in a footnote that the verb is not attributed to God. Of those that assume God’s capacity for anger, one translator says it refers to those outside the ahl e kitab, i.e. those who are not Jews or Christians? So, most translators suggest God has a strong negative emotion of anger or wrath. Is the idea of an angry or wrathful God accurate? Is it an attempt to anthropomorphize God? Or is it a weak attempt to explain the large problem of suffering? Or it is simply an unintended consequence of the authoritarian era that most Muslim scholars have historically inhabited? In this case, BioIslam relies on the minority translation since the translator is highly respected in both the Traditionalist and secular academic communities.

Mawla

What does the word mawla mean? According to one scholar it could mean any of the following: master, patron, friend, client, or protege.43 Shi’a prefer the first two interpretations, Sunnis the remaining ones. As discussed further in Pitfalls – Inconvenient Implications, this word is pivotal to interpreting the intent of the hadith of Ghadir Khumm, a key point of disagreement between the Sunni and Shia sects.

Idribuhunna

Does it mean ‘strike’ or strike a new path? All Traditionalist translators opt for variations of strike. Surprisingly, the two translations most respected by academics, The Study Quran and Prof. Haleem’s work, use hit/strike. Some modernist translators clarify it is a mild, even symbolic, form of striking, but as we see later in Pitfalls – Inconvenient Implications the ulama historically did not speak out against what most women would consider harsh striking, which has led to a little-acknowledged problem of widespread domestic violence in many or most Muslim (and non-Muslim) communities. A few new translations of the Quran state that it means strike a new path; they include Laleh Bakhtiar’s work and that of others associated with the Quranist movement.

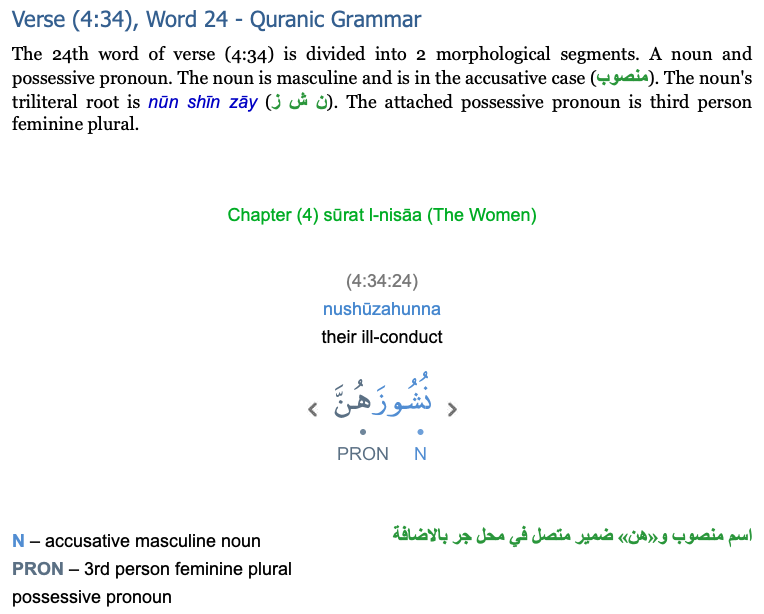

Mutawaffika

Does it mean Isa/Jesus ﷺ ‘died’ or was ‘taken away’? All Traditionalist translators cite the latter. A notable exception, the Quranists, believe it is the former. BioMuslims side with the Traditionalists on this one.

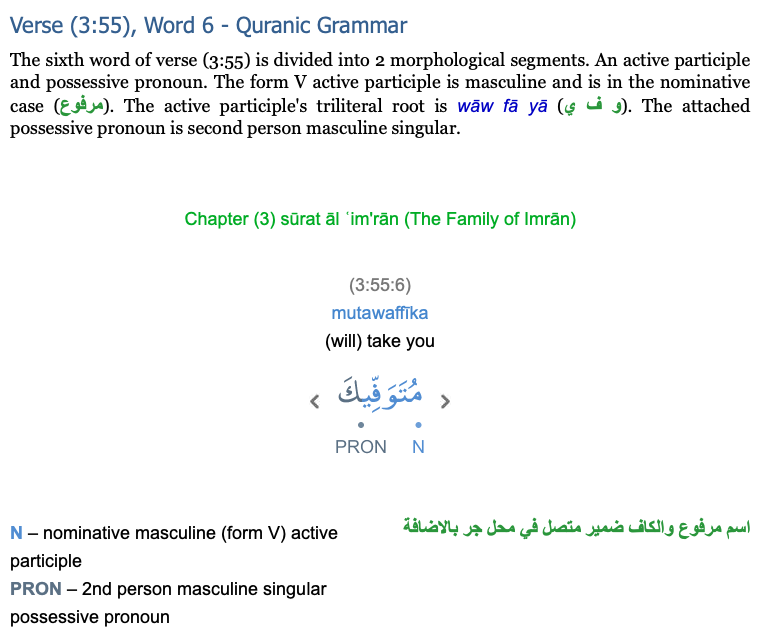

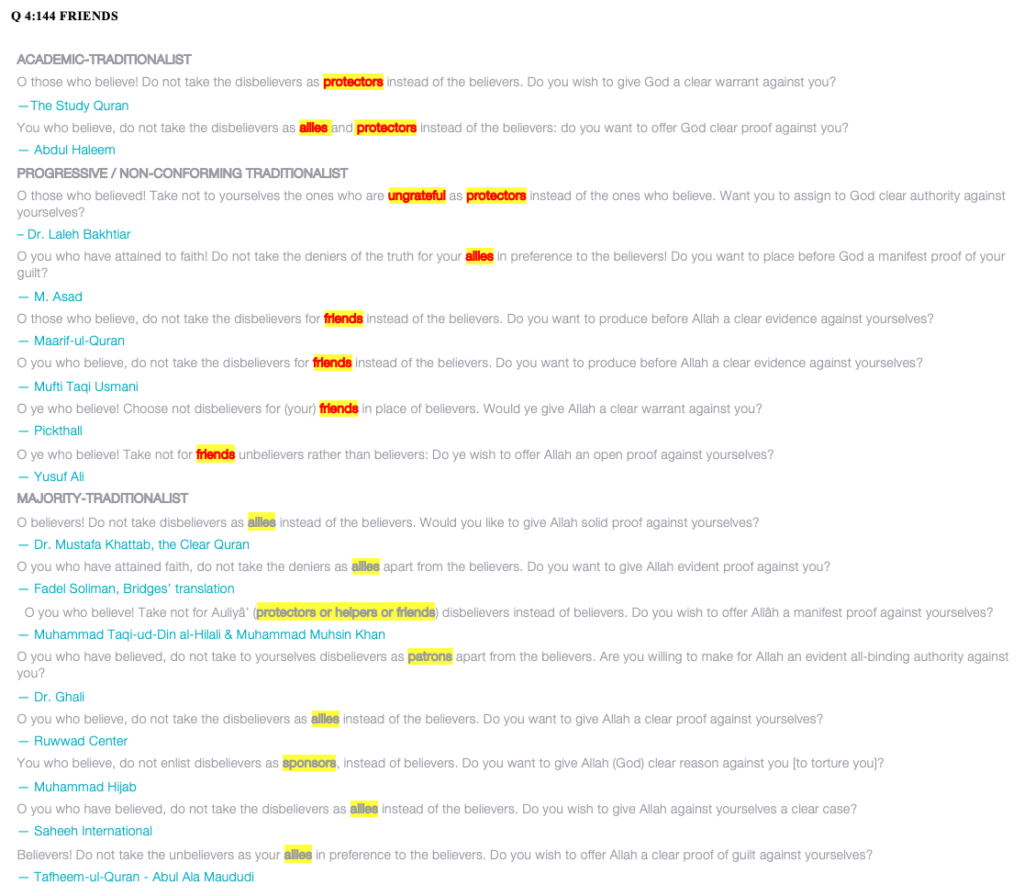

Auliya

Another example of the consequence of this problem is the verse 4:144 – depending on which translation you use, the verse will state Muslims cannot have non-Muslim friends or allies or protectors or sponsors or patrons, which is a large difference. If we account for the fact that the context for the revelation of the verse, based on other verses in the Quran itself, is that the verse was revealed at a time of civil conflict, the correct translation is likely to be allies / protectors.

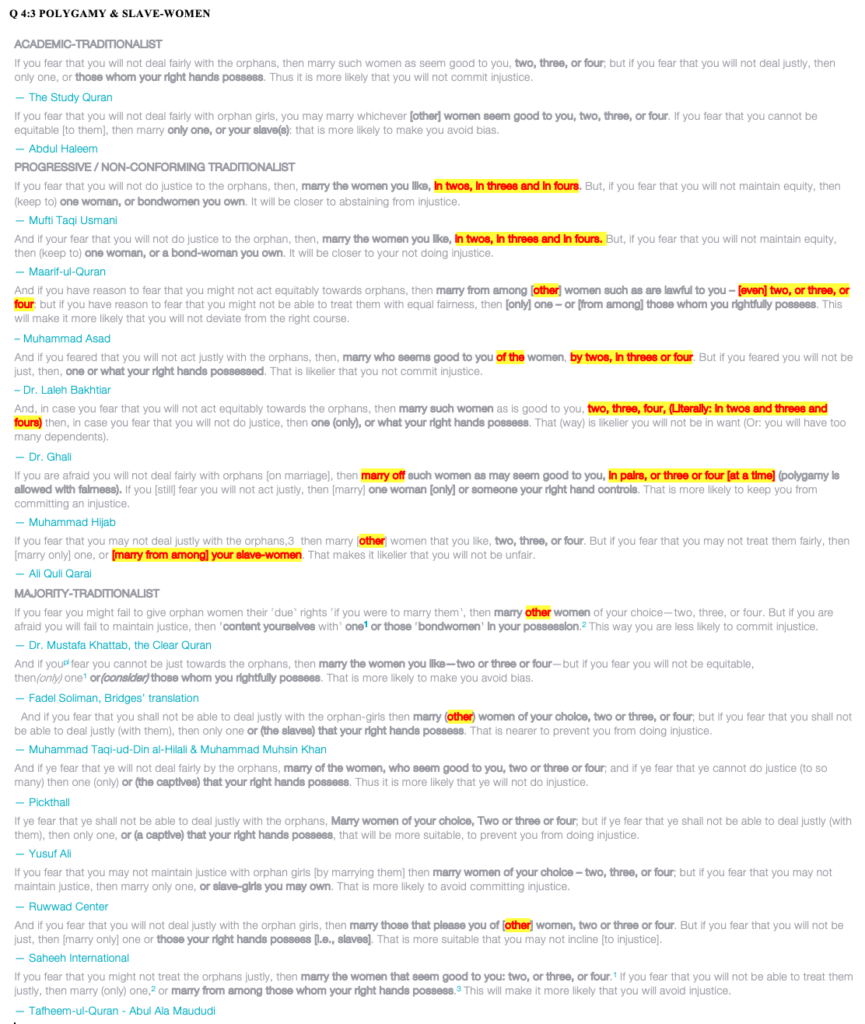

Marry Four or “In Fours”? Slaves?

There is disagreement on how to translate the infamous verse that Traditionalists claim allows for marrying up to four wives. Some translators believe it should be read as “in fours”, which has led a tiny minority of ulama to assert that the limit of four does not apply, i.e. unrestricted polygyny is allowed. Others, especially women and progressive Muslims, believe that the conditional phrase at the beginning of the verse limits this discussion to extreme social conditions that have resulted in too many orphans. Based on this hard-to-parse verse alone, it is difficult to arrive at a definitive conclusion.

However, BioIslam favors monogamy since 1) a later verse mentions the near impossibility of fair treatment of multiple wives (Q. 4:129), and 2) evolutionary biologists have observed that when polygyny occurs under normal demographic conditions, i.e. when the sexes are in approximately equal ratio44 it exacerbates inequality and increases violence.45 Although the ulama could have used their flawed theory of abrogation to argue that 4:129 abrogates 4:3 and polygyny, they did not.

On the second half of the verse, relating to slaves, once again the translation problem strikes. Is the verse licensing sex with slaves an alternative to marriage, or the inverse, that marriage is a prerequisite to sex with a slave. In the pre-abolition era, i.e. most of Islamic history, most ulama unfortunately held the former position. Based on this hard-to-parse verse alone, it is difficult to arrive at a definitive conclusion. But, as noted in other pages, given the abolitionary impetus of the Quran, and BioIslam’s belief that the Prophet ﷺ eradicated riq-slavery in his vicinity, the latter appears to be a better interpretation.

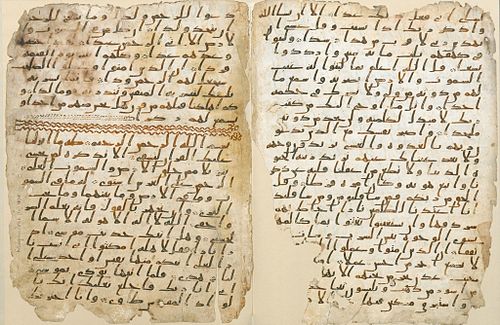

The Rasm Problem?

Does the consonantal form (rasm) of the first Uthmanic codex of the Quran contribute to the Translation Problem? For those unfamiliar, the initial written versions of the Quran, did not have orthography or vowels.46 At some unknown date, perhaps at least 50 years after the Prophet ﷺ, orthography was gradually introduced. However, it remained inadequate, at least until a project to substantially improve orthography was initiated by Caliph al-Walid in 95/71447. Orthography was finalized by the aforementioned Farahidi (d. 164/786), who also authored the first lexicon, about 150 years after the Prophet ﷺ. After his orthographical project, “It was considerably less ambiguous than the old system, in which the dots had to perform various functions. With al-Halil’s (Farahidi’s) reform, the system of Arabic orthography was almost completed and, apart from a very few additional signs, it has remained essentially the same ever since (parenthesis is mine).”48

What problems might have occurred due to the lack of orthography in the first half century? It is widely agreed upon that there was a strong oral tradition of memorizing the Quran, which preserved the integrity of the revealed verses. The oral tradition was exacting, but can we rely on it to signal how the punctuation applies? Two examples are offered below; both suggest that if the orthography accepted by Traditionalists is incorrect in its placement of just one comma, verses 3:7 and 89:27-30 would take on a substantially different and mystical meaning.

A leading scholar notes, “In the debate over the nature of the Qur’an, there were political factors at work alongside the theological ones, but even the most literalist reading of the Qur’an had to deal with the problem of interpreting certain verses metaphorically… The Qur’an itself (Q. 3:7) alludes to the difficulty of interpreting the passages that contain symbolism, in contrast to the portions of the Qur’an they have clear instructions…”. So depending on the location of a comma and a period in 3:7, it could mean either that “only God can know the interpretation of the symbolic passages; all that believers can do is have faith in it without asking further questions” or that those ‘who possess an inner heart (lubb)’ can heed and recall the message… a reminder that there is a special knowledge that permits access to the divine…” He goes on to say, “… it is remarkable how what amounts to the placing of a punctuation mark in this Quranic verse can open up a chasm between opposing positions” (emphasis mine). 49

Another leading scholar illustrates how changing the location of a comma can substantially change the meaning of a Quranic verse (89:27-30), from a plain reading to a mystical Sufi interpretation, from a belief in residing in a physical garden in the afterlife, to a spiritual state of joy achievable in the present. “The Arabic language of the Quran did not use commas and periods. There are many places in the Quran where pausing after one word instead of another can radically change the meaning of the whole verse. One of the clear examples is in the verse that is often employed upon hearing of a death. The verse addresses the ‘souls at peace,’ who are pleased with God as God is pleased with them. Enter inside, O my servants, and you have entered My garden. Bu many mystics, including Rumi, read the same verse differently. In reading it, as it were, without a comma, they arrive at a radically different, and more powerful, reading: Enter inside My servants, and you have entered My garden. In this reading, God’s supreme reward, the garden of paradise, is found when we enter inside the heart of one of God’s beloveds, those who are pleased with God and with whom God is pleased. in this mystical reading, the garden is not a physical destination but a spiritual state that we discover here and now.”50

Hence, a punctuation problem combines with the Dictionary Problem to create the Translation Problem. If the current orthography of the Quran does not reflect the original intent of Allah ﷻ, then we must be intellectually honest – we must acknowledge that BioIslam’s amystical interpretation of the five Inside Pillars might also be erroneous. However, wholesale error is unlikely, but errors in fixing punctation are plausible. We proceed on the assumption that the oral tradition was precise enough to ensure that orthography was mostly correctly applied to the rasm, and in places where it did not, the errors are of a small enough scale to get diluted out by the multi-level induction process of LPs.

The Only Escape: Dilute the Error

No matter which interpretation of Islam we choose, whether BioIslam or any other, we cannot escape the Dictionary-and-Grammar Problem (and by extension the Translation Problem). As noted above, this is due to the fact that the basic form of written Arabic, including its vowels, was not finalized until 150 years after the Prophet ﷺ. Even beyond that date, loanwords continued to be imported from other parts of the far-flung empire; the first extant Sirah book by Ibn Hisham (d. 218/833) employed more than 200 loanwords.51 Given this unfortunate reality, we should be wary of being too certain about what some verses really mean. Their controversial nature, whether in the past or present, originates in early disagreements about language and meaning. Although only a minority of verses suffer this problem, they are pivotal to the choices we need to make today on how to construct a future-focused theohumanistic society, one that prioritizes the Big Five problems. Hence the best way to deal with controversial verses is to view them in the holistic context of the Quran and the LPs that underly it.

In other words, to the degree that the original meaning of certain crucial words like mawla can never be agreed upon, it is best to honestly acknowledge we can’t possibly know, given the late date at which the first books of dictionary and grammar were published. Instead of partisan insistence of a fixed meaning, we can rely on the Quranic LPs for guidance. Through BioIslam’s process of generalization is based on inductive logic, the uncertainty associated with certain words or phrases gets diluted out in favor of higher-order messages that bubble up from the broad array of missives and directives in the Quran. Thus, in our march towards the message sent by our Creator, the ‘higher road’ is based on Latent Principles and Inside Pillars, whereas the ‘lower road’ is based on narrow argumentation built around specific words, phrases or ayats.

Our Diluted Translation — The verses we cite are primarily from the Prof. Abdul Haleem translation sourced from Quran.com, which is one of the most academically-sound Traditionalist translations. On occasion, we have noted and used translations from The Study Quran, which is being increasingly used in the academic world; it attempts to be non-sectarian and offers a valuable summary of divergent Traditionalist tafsir interpretations, but has not yet been uploaded onto Quran.com. Where necessary, we have noted the use of the Saheeh International translation to aid in clarity. In pivotal cases, we have reviewed all translators on Quran.com, plus a few others that are not, including especially The Sublime Quran by Laleh Bakhtiar, which offer’s a valuable woman’s perspective; although it is dismissed by both ulama and secular scholars. Surprisingly, it has received a fatwa of approval from the bastion of Traditionalism, Al Azhar University – which some scholars believe confirms corruption in the world of fatwa issuance. We have also on rare occasions noted and cited the Quran translation by The Monotheist Group, which is authored by the brave founders of the (anti-Traditionalist) Quranist movement, but has, to the best of our knowledge, received no validation from secular academics or Arabic linguists. Although the Quranists have made important contributions to reforming Traditional Islam, their key shortcoming might well be the claim to a radically improved translation of the Quran, which is sadly infeasible due to the Dictionary Problem.

As acknowledged at the outset, even though we critique the well-intentioned Traditionalists for being tripped up by the dictionary-and-grammar problem, we too rely on the Arabic-to-English translations they have published — although this is an imperfect choice, it is superior to relying on a single translator no matter how good that translator’s credentials are. Further, since translation error is inevitable, the downside is limited since errors are more likely to be diluted out through the multi-verse induction process, as opposed to the reinforcement of errors that is likely to occur if we rely on a deductive approach based on a single translator.

Footnotes

- As an eminent scholar of Persia comments on the consequences of the Arab conquest, “The Persian language survived, while many other languages in the lands the Arabs conquered went under, to be replaced by Arabic. Persian changed from Middle Persian, or Pahlavi, of the Parthian and Sassanid periods, acquired a large number of loan words from Arabic, and re-emerged after two obscure centuries as the elegantly simple tongue spoken by Iranians today. As for the Persian language, some would say that Persian became a new language, much as English transformed in the Middle Ages after the Norman conquest” (emphasis mine). Michael Axworthy, A History of Iran, 68.

- Richard Frye, The Golden Age of Persia, 150.

- Oliver Leaman, Arabic Language, in Encyclopedia of Islam, 51, 52.

- There is a separate scholarly debate about whether Arabic contains foreign loanwords from the time prior to or during the period of Prophecy. BioIslam’s accepts the philological view on this, i.e. that “there are indeed foreign words in the Quran, but they were naturalized in Arabic long before the revelation.”, as noted in Michael Carter’s chapter on Foreign Vocabulary in Rippin’s The Blackwell Companion to the Quran, 122.

- Shk. bin Bayyah, translated by Shk. Hamza Yusuf, The Centrality of Language in Islam’s First Years, essay in Renovatio, Dec, 2018. He says “our tradition holds that the Caliph Alī taught Abū Aswad al-Du’alī to categorize Arabic into nouns, verbs, and prepositions and particles, and then said, “Proceed in this manner” (unĥu hādhā al-naĥw).”

- ibn Khaldun, The Muqaddimah, as translated by Franz Rosenthal, free pdf version, 742, 1196

- ibid., 744

- Ira Lapidus, A History of Islamic Societies, 118.

- Sibawayhi is properly known as Abū Bishr ʿAmr ibn ʿUthmān ibn Qanbar Al-Baṣrī, and was born in Hamadan, modern-day western Iran. Farahidi was an Omani-Arab, properly known as al-Khalil ibn Ahmed al-Farahidi, and also known as al-Halil ibn ‘Ahmad. Farahidi’s book was completed posthumously by his student al-Layth.

- Tim Mackintosh-Smith, Arabs, 290-91

- ibid., 296-97

- Kees Versteegh, The Arabic Language, 75.

- Tim Mackintosh-Smith, Arabs, 201

- ibn Khaldun, op. cit., 736

- MG Carter, chapter on Arabic Grammar, in Religion, Learning and Science in the Abbasid Period, 122.

- Ramzi Baalbaki, The Legacy of the Kitab, 231.

- ibn Khaldun, op. cit., 718

- Fred Donner, The Quran in recent scholarship, in Donner and Reynolds, The Quran in its Historical Context, 44.

- Ignaz Goldziher, The Zahiris – Their Doctrine and History, 176-177.

- Jonathan Owens, The Foundation of Grammar, 4.

- Lutz Edward, Sibawayhi’s Observations, Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies, 3, 2000, 63.

- Fred Donner, The Quran in recent scholarship, in Donner and Reynolds, The Quran in its Historical Context, xi.

- Versteegh, op. cit., 63.

- Aryeh Levin, Sibawayhi’s Attitude to the Language of the Quran, in Israel Oriental Studies XIX, 270.

- Fred Donner, The Quran in recent scholarship, in Donner and Reynolds, The Quran in its Historical Context, 37.

- Ramzi Baalbaki’s review of Monique Bernards book,“Changing Traditions”, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 119, 1999, 532-533.

- Bosworth et al, The Encyclopedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume IX, 1997, 524.

- Versteegh, op. cit., 64.

- MG Carter, chapter on Arabic Grammar, in Religion, Learning and Science in the Abbasid Period, 126.

- Jonathan Owens, The Foundation of Grammar, 9.

- H.A.R. Gibb, The Social Significance of the Shuubiya, in Studies on the Civilization of Islam, 62

- MG Carter, Sibawayhi (Makers of Islamic Civilization), 11

- Although there currently remains plenty of both ethnic and political tensions between Persians (Iranians) and Arabs (especially Saudis), this is not generally viewed a continuation of the ancient Shu’ubiyya problem.

- Roy Mottahedeh, The Shu’ubiyah Controversy and the Social History of Early Islamic Iran, International Journal of the Middle East Studies, 1976, 161-182

- Michael Axworthy, A History of Iran, 79.

- Edward Lipinski, Arabic Linguistics, A Historiographic Overview, 28.

- Versteegh, op. cit., 55 and 60. On a side note, the tafsir of Mujahid ibn Jabbar, is lost to history, although traces of it are found in Tabari’s comprehensive tafsir, published nearly two centuries later. Also, Mujahid was a student of the sahaba ibn Abbas, who also reportedly wrote a tafsir, although the latter one might be falsely attributed to him by al-Fayruzabadi (d. 1414). The latter was the author of a very famous dictionary, al-Qamoos, which highlights the Historical Truth problem; if a respected scholar could falsely attribute to a respected sahaba, or even be falsely accused of doing that (one of those options must necessarily be true), what hope is there for knowing the real story?

- Versteegh, op. cit., 61.

- Versteegh, op. cit., 113.

- Mustafa Shah, Philological Endeavours of the Early Arabic Linguists: Theological Implications of the tawqif–istilah Antithesis – Part I, Journal of Quranic Studies, Vol. 1, No. 1, 1999.

- The Quran says, “And Solomon inherited David. He said, “O people, we have been taught the language of birds, and we have been given from all things. Indeed, this is evident bounty.” (Q. 27:16)

- Tim Mackintosh-Smith, Arabs, 395-96

- See “The First Muslims” by Prof. Asma Afsaruddin, p. 14-15 and p.203, for the varied meanings of mawla and for which Hadith books include and exclude the Ghadir Khumm incident.

- There is no evidence to believe that the sex ratio was anything other than normal. While apologists for polygyny contend that war deaths skewed the ratio toward females, they neglect to account for the high mortality rate of maternity.

- David P. Barash, Out of Eden: The Surprising Consequences of Polygamy.

- Without orthography, you cannot distinuguish between letters baa/taa/thaa/nuun/ya or jeem/haa/kha or seen/sheen etc.

- Ira Lapidus, A History of Islamic Societies, 38.

- Versteegh, op. cit., 56-7.

- Carl Ernst, Sufism, 37-38.

- Omid Safi, Radical Love, xxxiii-iv.

- Versteegh, op. cit., 73.